and

who reject anal penetration, promiscuity, and effeminacy

NIKOMACHEAN ETHICS

and

CICERO'S

TUSCULAN DISPUTATIONS

by

Bill Weintraub

PROLOGUE

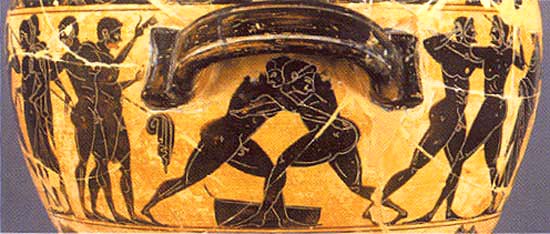

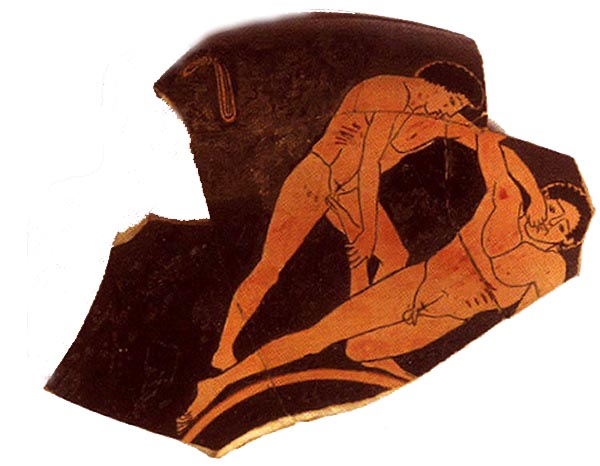

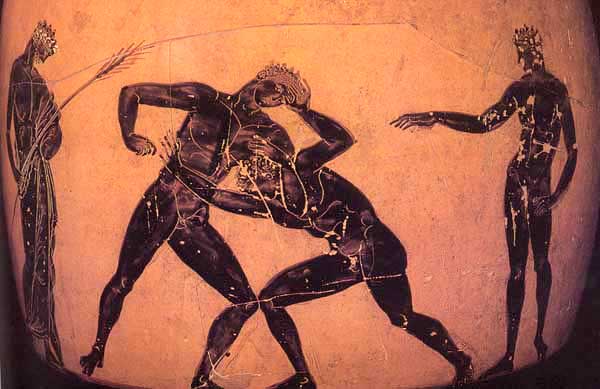

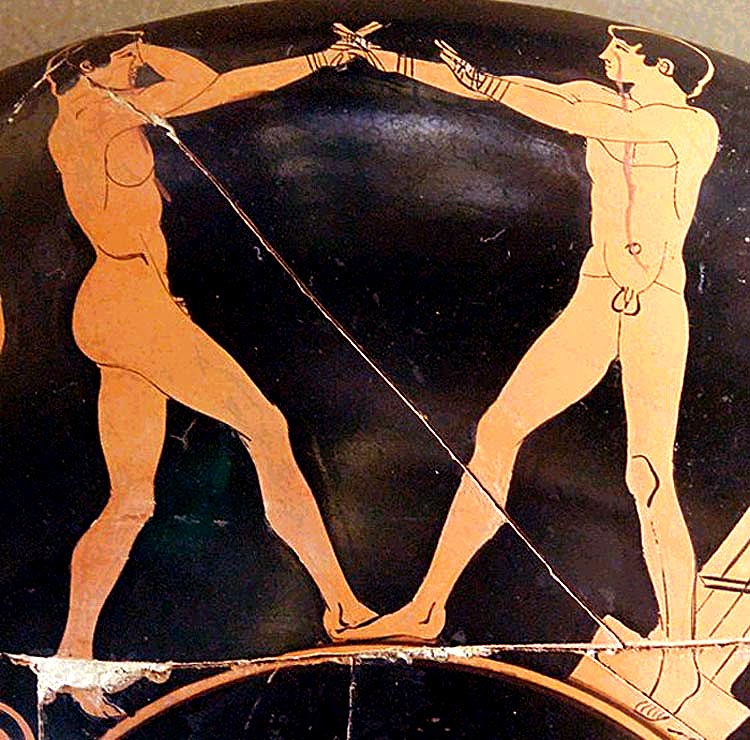

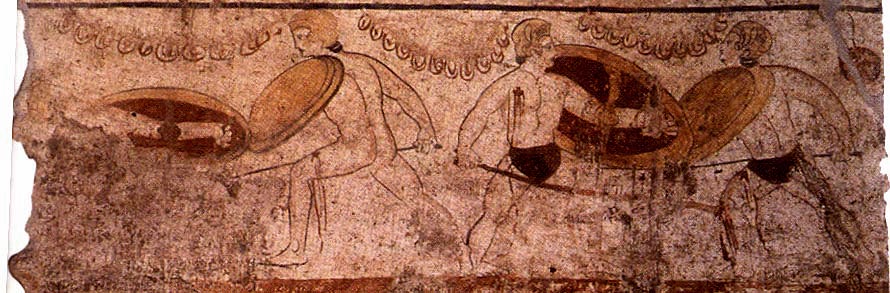

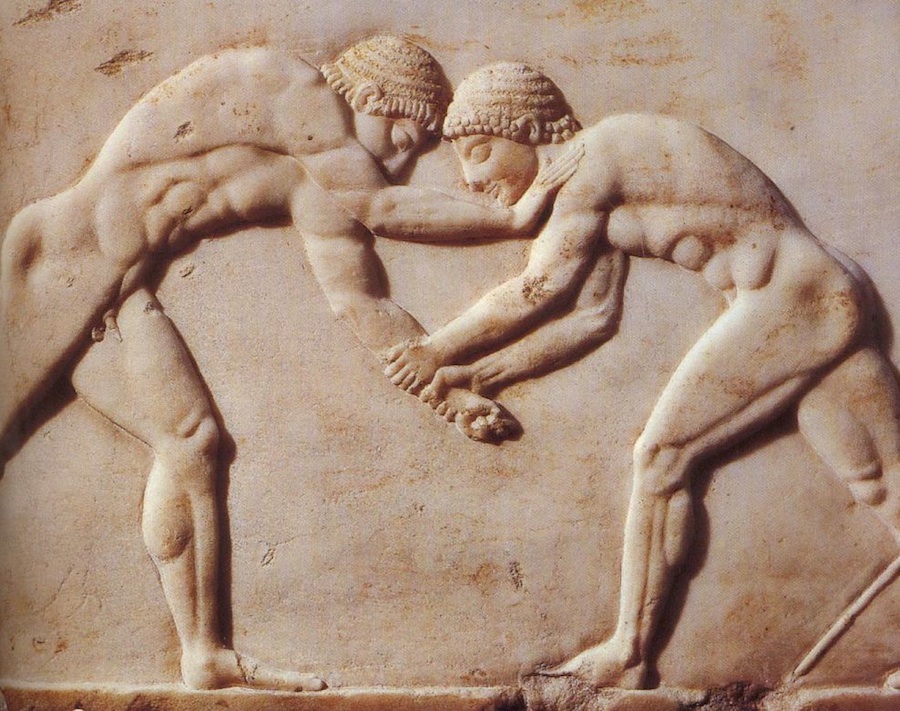

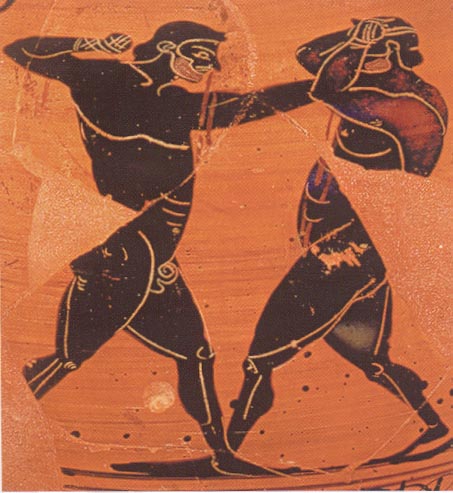

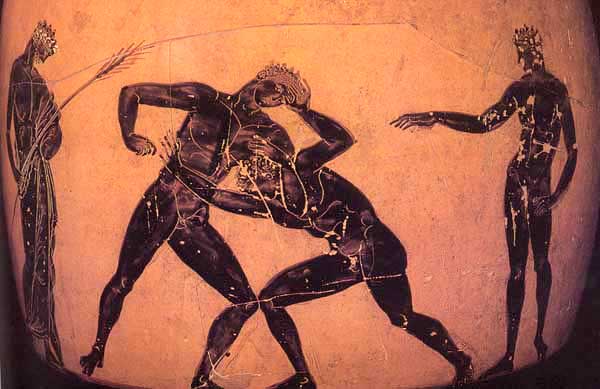

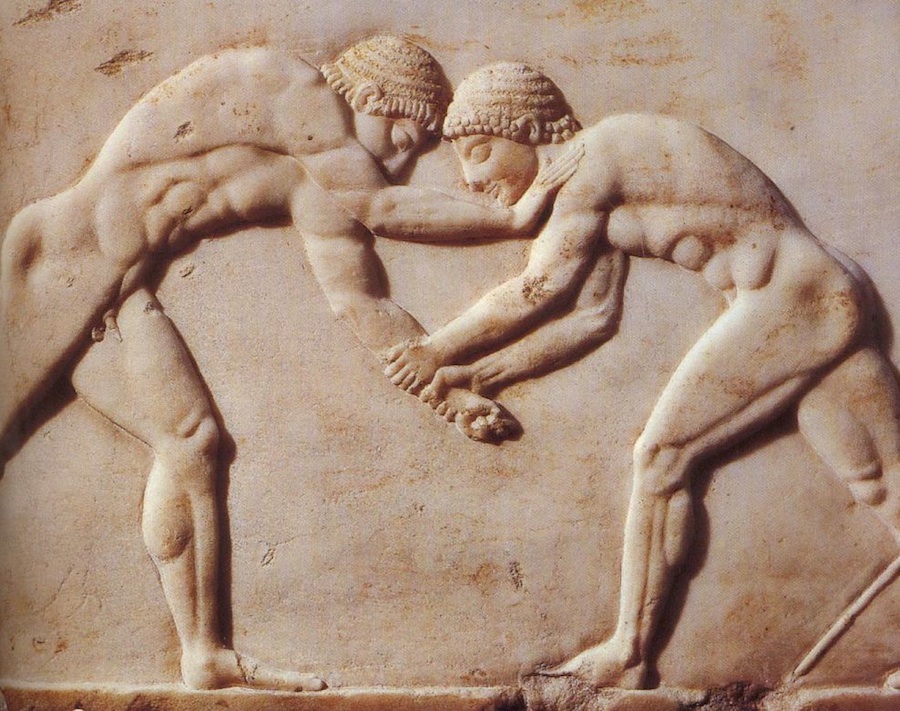

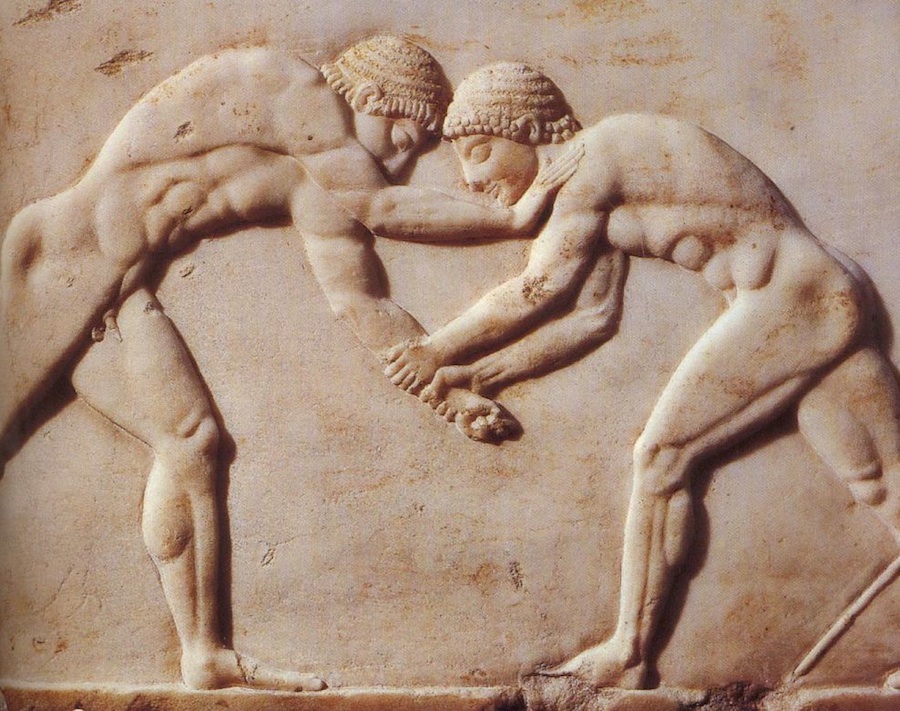

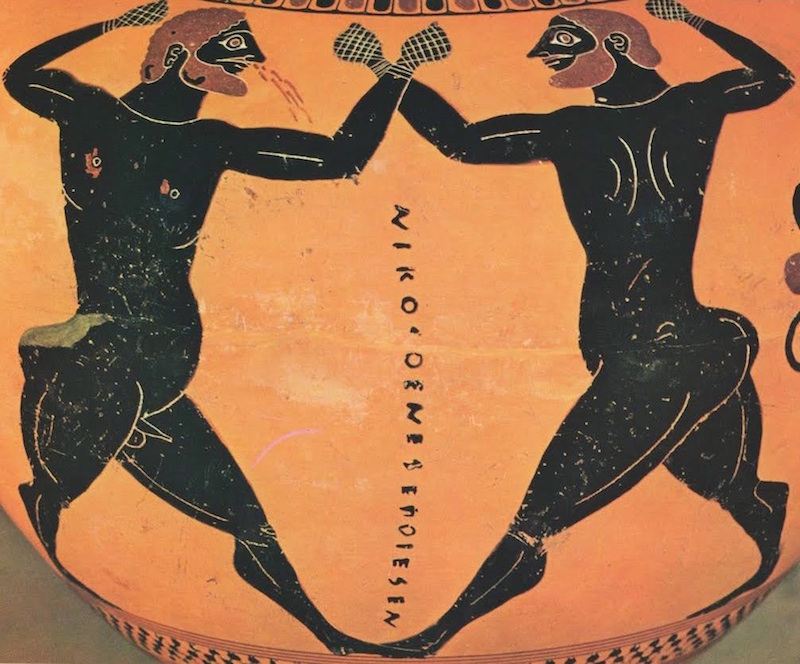

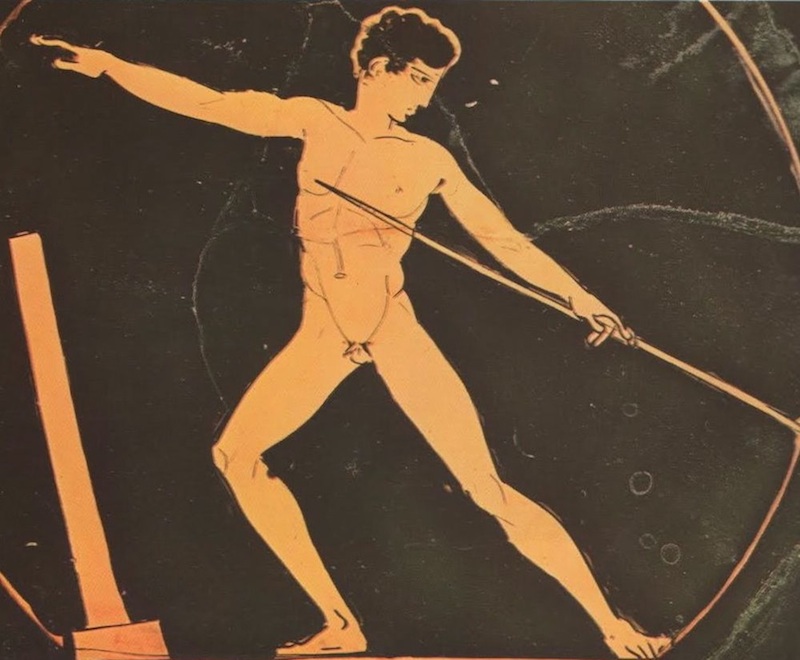

XX. Will you, though you have seen boys in Lacedaemon, young men at Olympia, barbarians in the arena submitting to the heaviest blows and enduring them in silence -- will you, if some pain happen to give you a twitch, cry out like a woman and not endure resolutely and calmly?

"It is unbearable ; nature cannot put up with it."

Very well.

Boys endure from love of fame, others endure for shame's sake, many from fear, and yet are we afraid that nature cannot put up with what so many have endured in such a number of different places?

Nature in fact not only puts up with but even demands it ; for she offers nothing more excellent, nothing more desirable than honour [honestas], than renown [laus], than distinction [dignitas], than glory [decus]. By all this number of terms there is only one thing that I want to express, but I employ a number, in order to make my meaning as clear as possible.

What I want to say in fact is that far the best for man is that which is desirable in and for itself, has its source in virtue or rather is based on virtue, is of itself praiseworthy, and in fact I should prefer to describe it as the only rather than the highest good. Moreover, just as we use language like this in speaking of what is honourable [honestum], so we use the opposite in speaking of what is base [turpe] : there is nothing so revolting, nothing so despicable, nothing more unworthy of a human being.

~Cicero, Tusculan Disputations. 2.46, translated by JE King.

Μarcus Tullius Cicero (106 - 43 BC) was a Roman orator, lawyer, and politician (and a philosopher). He was the head of the Roman bar, and very ably served his country, including as consul in 63 BC, and provincial governor.

In 45 BC, his personal life in ruins due to a bitter divorce from his wife Terentia and the death of his beloved daughter Tullia, and with no place for him in public life under Caesar's dictatorship, he turned to philosophy, and in very short time produced more than seven books, including The Tusculan Disputations.

The Disputations take place at Cicero's villa in Tusculum, and are in the form of a dialogue between "M" -- probably Marcus or Magister -- and a youth, "A" -- almost certainly an Adulescens -- that is, a young Man of about 18 years.

In Book II of the Disputations, M asks the youth if he believes that pain is the greatest evil, and when the youth says Yes, M responds -- Really -- greater than dishonour or disgrace ?

The youth immediately recants, and agrees with M that dishonour is a far greater evil.

M then presents many examples of how a Man should behave towards pain -- all of them illustrations of Aristotle's point in the Nikomachean Ethics (ca 330 BC) that the supreme moral virtue of Manliness -- is about the facing and endurance of pain.

And that we learn to endure pain -- through enduring pain ; which is to say that the possession of any moral virtue, including Manliness, is a function of training and habit.

In order to understand the ancient Greeks and Romans, we have to understand these two key points : that dishonour is a far greater evil than pain, and that Manliness is in its essence a habit, the result of many years' training in facing and enduring pain.

Cicero :

A. I consider pain the greatest of all evils.

M. Greater even than disgrace?

A. I do not venture to go so far as that and I am ashamed of having been dislodged so speedily from my position.

M. You should have been still more ashamed had you clung to it. For what is more unworthy than for you to regard anything as worse than disgrace, crime and baseness? And to escape these, what pain should be, I do not say rejected, but should not rather be voluntarily invited, endured and welcomed?

A. I am entirely of that opinion.

~Cic. Tusc. 2.14, translated by JE King.

. . .

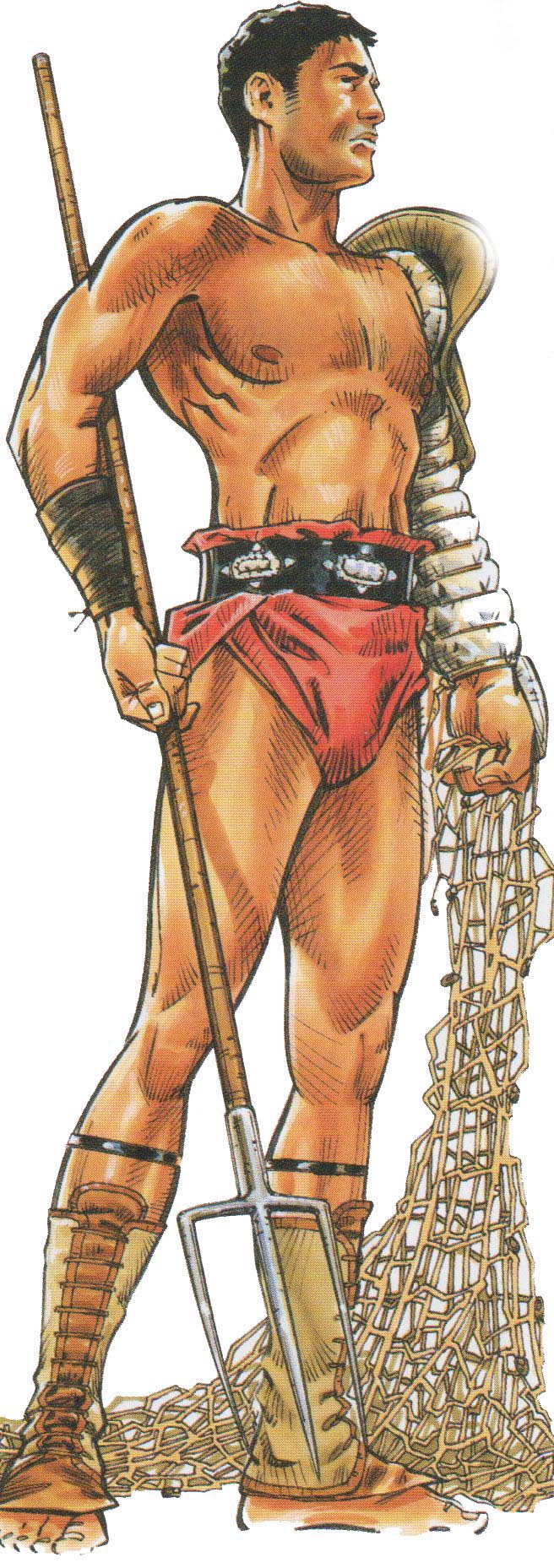

Cicero then discusses the benefits of habit and training among two groups : Roman Legionaries ; and Gladiators :

Cicero :

M. Military service in fact -- I mean our own and not that of the Spartans who march to a measure accompanied by the flute, [1] and no word of encouragement is given except with the beat of anapaests [2] -- as for our "army" (exercitus -- training) you can see first what it gets its name from [3] ; then the toil, the great toil of the march ; the load of more than half a month's provisions, the load of any requisite needed, the load of the stake for intrenchment ; for shield, sword, helmet are reckoned a burden by our soldiers as little as their shoulders, arms and hands ; for weapons they say are the soldiers' limbs, and these they carry handy so that, should need arise, they fling aside their burdens and have their weapons as free for use as their limbs.

Look at the training of the legions, the double, the attack, the battle-cry, [4] what an amount of toil it means! Hence comes the courage in battle that makes them ready to face wounds. Bring up a force of untrained soldiers of equal courage : they will seem like women. Why is there such a difference between raw and veteran soldiers as we have lately had experience of? [5]

Recruits have usually the advantage in age, but it is habit which teaches men to endure toil and despise wounds. Nay, we see too wounded men frequently carried out of the line of battle, and the raw untrained soldier on the one hand uttering disgraceful lamentations however trifling his wound, whilst on the other hand the trained veteran, made more brave by the advantage of training, only wants the surgeon to put the bandage on him . . .

Footnotes :

1 The Spartans marched slowly to the sound of the flute, Thuc. V. 70. Cf. Milton, Par. Lost, I. 550:

Anon they move

2 The marching metre, as in the Spartan poet Tyrtaeus.

3 "Exercitando," -- Training -- according to Varro.

4 Called "baritus" and given when the lines engaged.

5 Cicero is thinking of Caesar's veterans and Pompey's untrained troops in 48 b.c.

~Cic. Tusc. 2.37, translated by JE King.

. . .

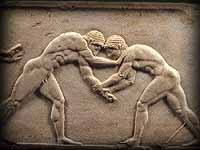

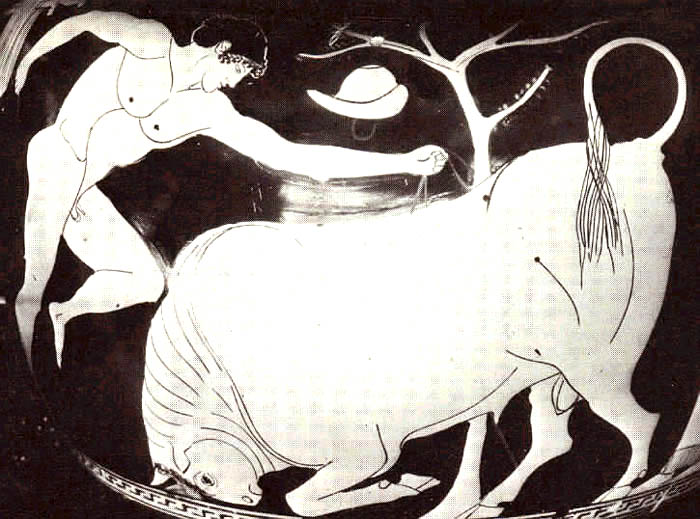

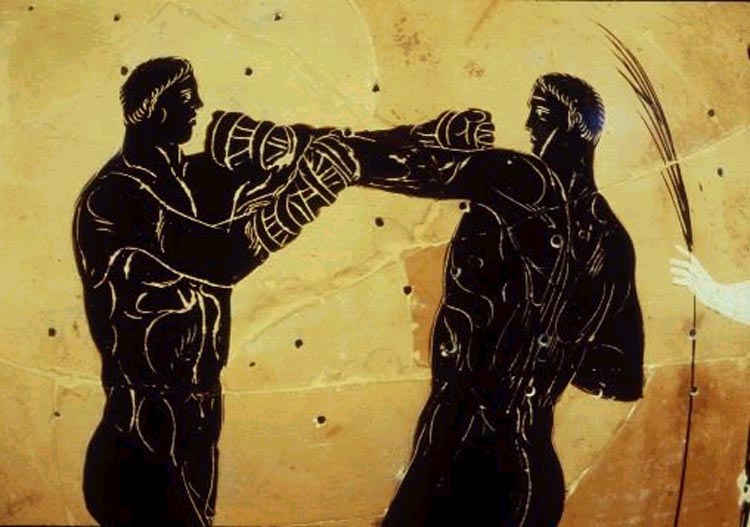

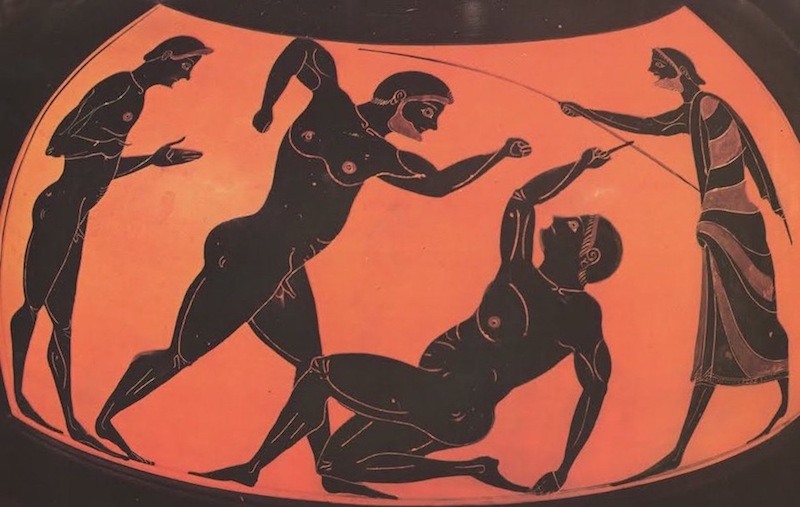

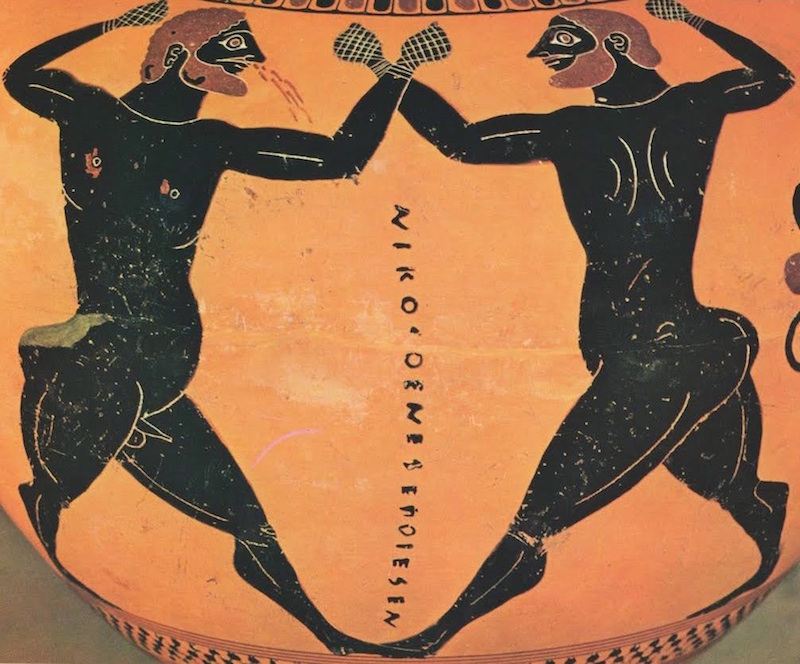

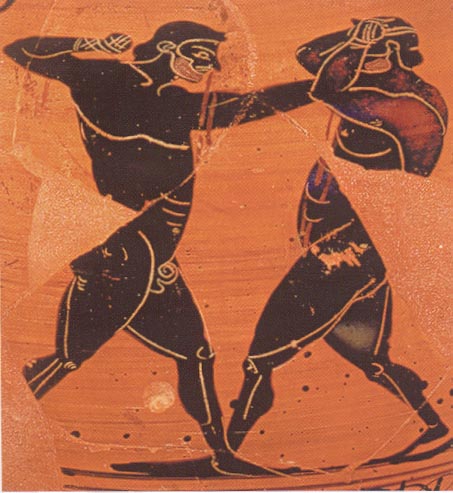

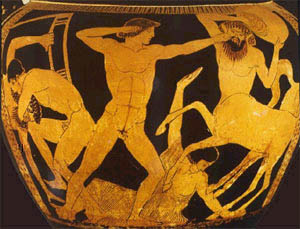

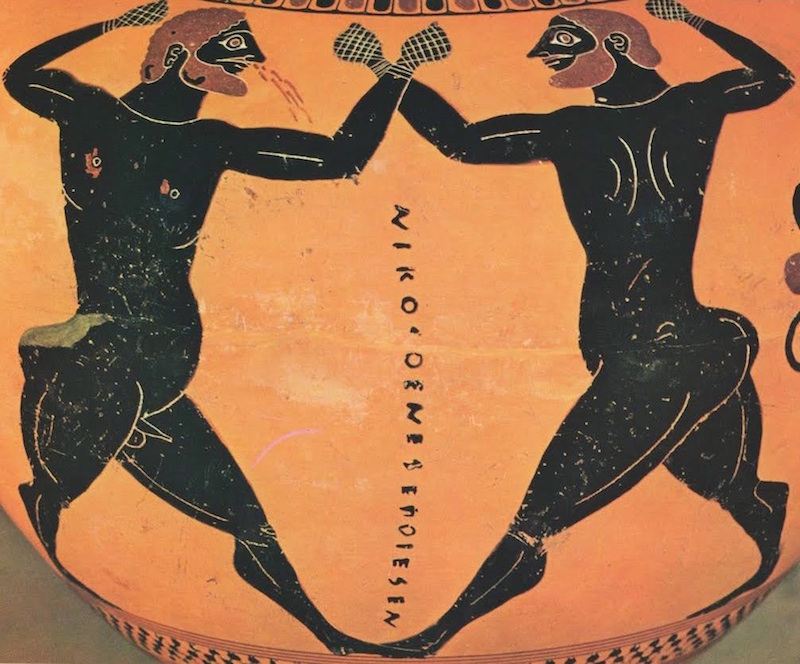

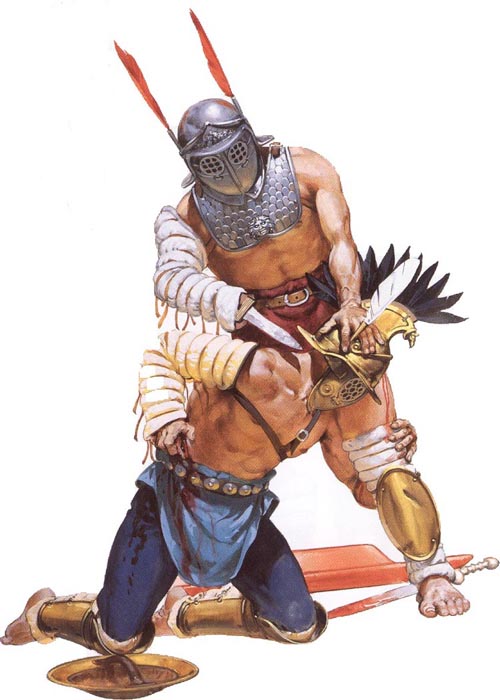

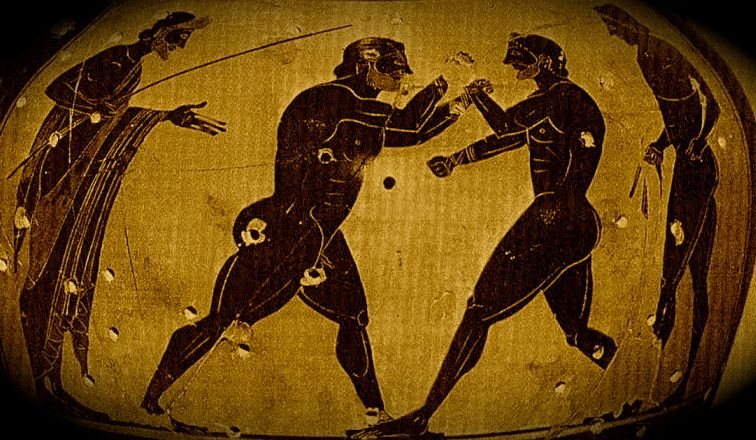

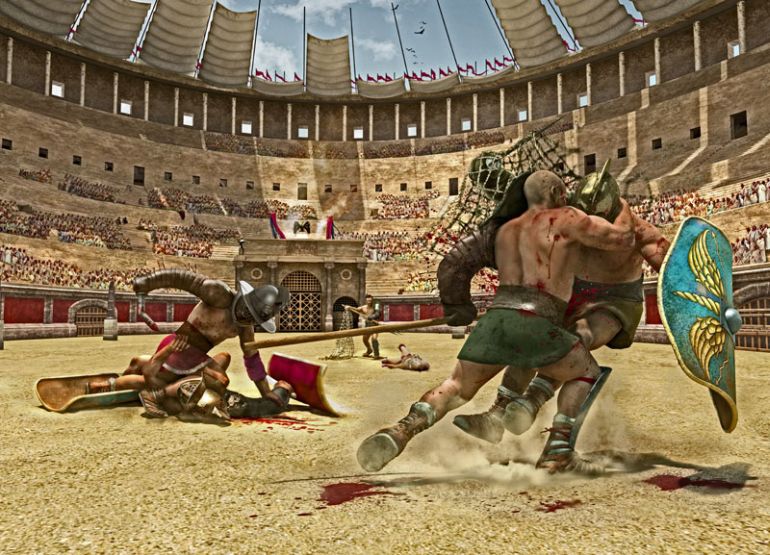

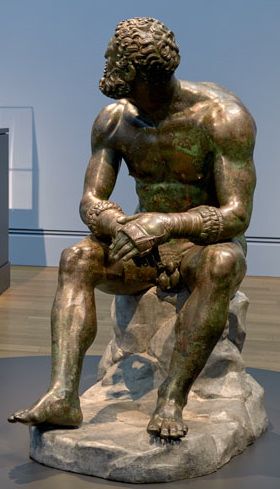

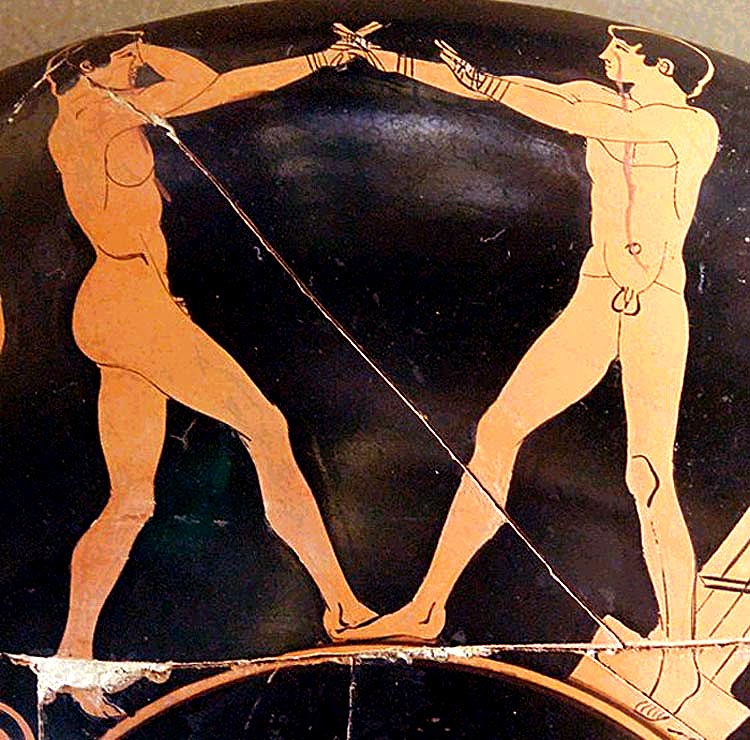

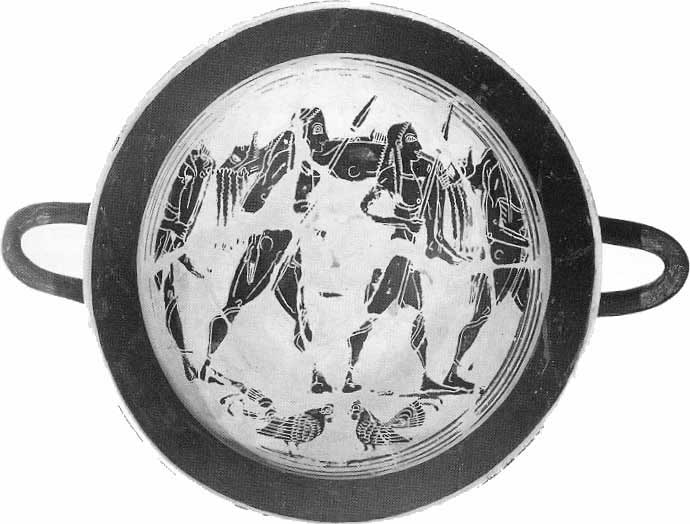

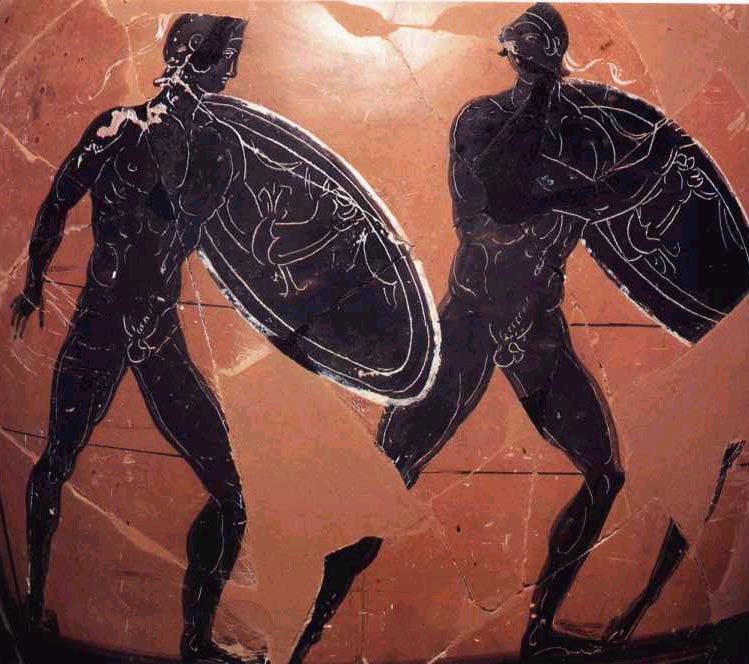

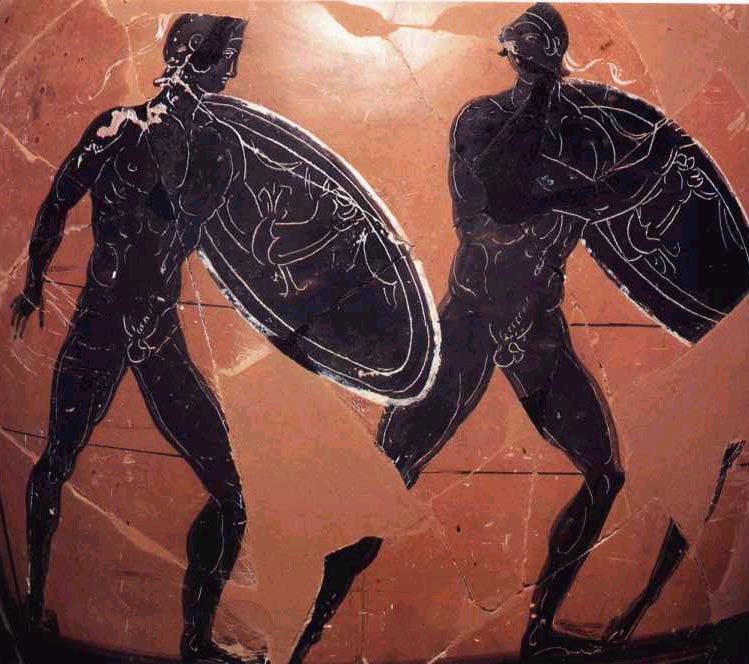

M. The force of habit is great. Hunters pass the night in the snow on the mountains : Indians suffer themselves to be burnt ; boxers battered by the gauntlets [2] do not so much as utter a groan. But why mention those who regard an Olympic victory as equal to the consulship of olden days? [3] Look at gladiators, who are either ruined men or barbarians, what blows they endure!

Footnotes:

2 The gauntlets were of ox-hide stiffened with lead and iron, cf. Virg. Aen. 5. 425.

3 Cicero means that in the old days the consulship was prized as the reward of merit : the dictator Caesar gave it to his friends and even appointed one of them consul for a single day.

See, how Men, who have been well trained, prefer to receive a blow rather than basely avoid it! How frequently it is made evident that there is nothing they put higher than giving satisfaction to their owner or to the people! Even when weakened with wounds they send word to their owners to ascertain their pleasure : if they have given satisfaction to them they are content to fall. What gladiator of ordinary merit has ever uttered a groan or changed countenance? Who of them has disgraced himself, I will not say upon his feet, but who has disgraced himself in his fall? [1] Who after falling has drawn in his neck when ordered to suffer the fatal stroke? [2] Such is the force of training, practice and habit. Shall then

The Samnite, [3] filthy fellow, worthy of his life and

be capable of this, and shall a man born to fame have any portion of his soul so weak that he cannot strengthen it by systematic preparation? A gladiatorial show is apt to seem cruel and brutal to some eyes, and I incline to think that it is so, as now conducted. But in the days when it was criminals who crossed swords in the death struggle, there could be no better schooling against pain and death at any rate for the eye, [4] though for the ear perhaps there might be many.

Footnotes:

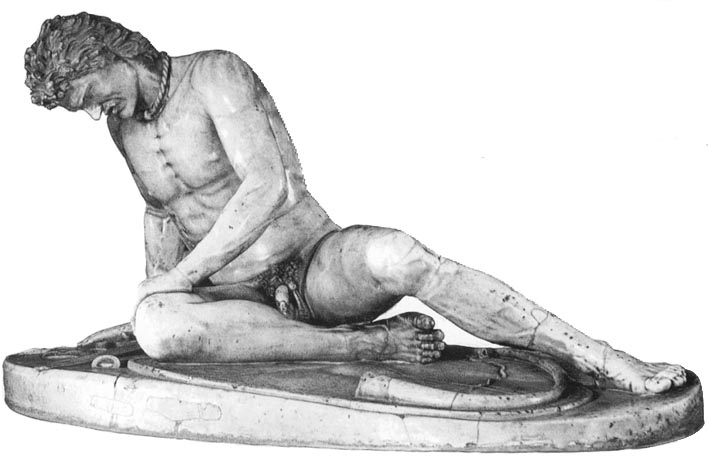

1 Cf. Byron, Child Harold's Pilgrimage, Canto IV. cxl.

I see before me the gladiator lie:

2 Cicero was killed in the proscription of 43 BC. When the executioners overtook him he thrust his neck as far forward as he could out of the litter and bade them do their work.

3 A verse of the satirist Lucilius. Samnis was a gladiator armed in the fashion of the old Samnites and often a native of Samnium, cf. App. II.

4 In Boswell's Journal Dr. Johnson says, "I am sorry that prize-fighting is gone out. . . . Prize-fighting made people accustomed not to be alarmed at seeing their own blood or feeling a little pain from a wound."

~Cic. Tusc. 2.40-41, translated by JE King

. . .

It is universally agreed then, not merely by the learned but by the unlearned as well, that it is characteristic of men who are brave [fortis], high-spirited, enduring, and superior to human vicissitudes to suffer pain with patience ; nor was there anyone, we said, who did not think that the man who suffered in this spirit was deserving of praise. When then this endurance is both required of brave men and praised when found, is it not base either to shrink from the coming of pain or fail to bear its visitation?

And yet, perhaps, though all right-minded states are called virtue [virtus], the term is not appropriate to all virtues, but all have got the name from the single virtue which was found to outshine the rest, for it is from the word for "Man" [vir] that the word Virtue [virtus] is derived ; but Man's peculiar Virtue is Fortitude, of which there are two main functions, namely scorn of death and scorn of pain. These then we must exercise if we wish to prove possessors of virtue, or rather, since the word for "virtue" is borrowed from the word for "man," if we wish to be Men.

~Cic. Tusc. 2.43, translated by JE King.

Bill Weintraub :

Cicero says that Man's peculiar Virtue is Fortitudo -- Fortitude -- scorn or contempt of death and of pain.

And we should understand that Fortitudo is Cicero's translation into Latin of the ancient Greek word andreia = ανδρεια -- Manliness -- one of the four platonic virtues, and the word which Aristotle uses for the Supreme Virtue -- which, again, is Manliness.

(And, as we'll see, Cicero agrees that Fortitudo is the Supreme Virtue.)

Fortitude, as discussed here by Cicero, may seem to us to be just one aspect of Manliness -- the Willingness and Ability to Fight, which in its Roman version is the Courage to Confront, and the Ability to Maim and/or Kill -- one's opponent.

But really, and while Fortitude may seem to be more about Willingness and Courage than it is about Ability, obviously one reason that the Man has scorn for death and pain -- is that he knows how to Fight.

Which is why Aristotle says that Training is of Supreme Importance.

And Cicero fully agrees.

Also :

It's no accident that Cicero, in talking to an adolescent Roman, cites Gladiators as examples of "men, who have been well trained, [who] prefer to receive a blow rather than basely avoid it."

Because that's what, to the Romans, Gladiators were meant to be : Examples and Exemplars of Fighting Men who put Honour before pain and death.

That they were low-born and criminals was very much to the Romans' point : even the low-born criminal could, with proper training, Fight Honourably, prefering "to receive a blow rather than basely avoid it."

To learn to stand up to blows face to face was, both to the Greeks and Romans, and as Aristotle says, of Supreme Importance.

The most important point that Cicero makes, however, is this :

And yet, perhaps, though all right-minded states are called virtue [virtus], the term is not appropriate to all virtues, but all have got the name from the single virtue which was found to outshine the rest, for it is from the word for "Man" [vir] that the word Virtue [virtus] is derived ;

but Man's peculiar Virtue is Fortitude, of which there are two main functions, namely scorn of death and scorn of pain. These then we must exercise if we wish to prove possessors of virtue, or rather, since the word for "virtue" is borrowed from the word for "man," if we wish to be Men.

So :

Although all right-minded states are called virtue [virtus], the term is not appropriate to all virtues, but all have got the name from the single virtue which was found to outshine the rest, for it is from the word for "Man" [vir] that the word Virtue [virtus] is derived ;

but Man's peculiar Virtue is Fortitude, of which there are two main functions, namely scorn of death and scorn of pain. These then we must exercise if we wish to prove possessors of virtue, or rather, since the word for "virtue" is borrowed from the word for "man," if we wish to be Men.

Manly Virtue, which is Manliness, outshines, says Cicero, all other virtues ; indeed, all other virtues "have got the name 'virtue' from the single virtue which was found to outshine the rest" ;

for it is from the word for "Man" [vir] that the word Virtue [virtus] is derived.

And Man's peculiar Virtue is Manliness, which includes Fortitude, and of which there are two main functions, namely scorn of death and scorn of pain.

These then we must exercise if we wish to prove possessors of virtue, or rather, since the word for "virtue" is borrowed from the word for "man," if we wish to be Men.

And what Cicero says could not be clearer.

IF WE WISH TO BE MEN, WE MUST POSSESS SCORN AND CONTEMPT FOR PAIN AND DEATH -- SCORN AND CONTEMPT WHICH IS ENABLED BY MANLINESS -- THE WILLINGNESS AND ABILITY TO FIGHT.

To Cicero, as to Aristotle, as to Xenophon, and indeed to any Greek or Roman, Fighting confers Manliness, while Manliness enables Fighting.

Aristotle :

If that isn't clear to you, we can make it clear by putting it in more colloquial terms :

Which means, at its most basic :

So :

ARISTOTLE :

FIGHTING CONFERS MANLINESS ; MANLINESS ENABLES FIGHTING.

CICERO :

ALL VIRTUE DERIVES FROM VIRTUS, WHICH IS MANLINESS, THE WILLINGNESS AND ABILITY TO FIGHT, AND TO SCORN DEATH AND PAIN.

Now :

I said that Fortitudo is Cicero's Latin translation of the ancient Greek word Andreia, which means Manliness, and that Cicero (106 - 43 BC) agrees with Aristotle (384 - 322 BC) that Manliness is the Supreme Moral Virtue, the Supreme Ethical Excellence.

So :

First we have a footnote from Cicero translator JE King, writing in 1927 :

Cicero invokes the four cardinal virtues, prudentia or practical wisdom (φρονησις), temperantia (σωφροσυνη), fortitudo (ανδρεια), iustitia (δικαιοσυνη), cf. III. 16.

Of all the Greek philosophers, Cicero most admired Plato, and the cardinal virtues are platonic.

Cicero :

Next will come Temperance, who is also self-control, and called by me a little while ago 'frugality,' and will not suffer you to do anything disgraceful and vile. But what is more vile or disgraceful than a womanish man?

Justice even will not suffer you to act in such a way ; there seems but little need for her in this case, but yet her plea will be that you are doubly unjust, since in demanding, in spite of your mortal origin, the attribute of the immortal Gods, and in repining at the repayment of the gift [ -- Life -- ] you have received as a loan, you are longing for what is not your own.

What answer moreover will you make to Prudence when she tells you that, for her, virtue is self-sufficient for leading a good life as well as a happy one? [1] And should Prudence be tied and bound to dependence on external things, and not owe her beginning to herself and return again to herself, so that in full self-dependence she seeks nothing from elsewhere, I do not understand why she should be held deserving of such passionate worship in words or such an eager quest in act.

1 The subject of Book V. It is the function of prudence to distinguish between bad and good.

~Cic. Tusc. 3.36, translated by JE King.

So :

Fortitude -- the scorn of death and pain -- is, among the Virtues, foremost of all.

And Fortitude is Andreia which is Manliness.

Why then, doesn't Cicero say so, by saying simply that Virtus is foremost.

Virtus, after all, does mean Manliness.

Except when it doesn't.

That's the problem.

In the Latin of his day, virtus can refer to any number of virtues :

Manly Virtue, which is Manliness, outshines, says Cicero, all other virtues ; indeed, all other virtues "have got the name 'virtue' from the single virtue which was found to outshine the rest" ;

All other virtues "have got the name 'virtue' from the single virtue which was found to outshine the rest" ;

for it is from the word for "Man" [vir] that the word Virtue [virtus] is derived.

And Man's peculiar Virtue is Manliness, which includes Fortitude, and of which there are two main functions, namely scorn of death and scorn of pain.

These then we must exercise if we wish to prove possessors of virtue, or rather, since the word for "virtue" is borrowed from the word for "man," if we wish to be Men.

And what Cicero says could not be clearer.

IF WE WISH TO BE MEN, WE MUST POSSESS SCORN AND CONTEMPT FOR PAIN AND DEATH -- SCORN AND CONTEMPT WHICH IS CONFERRED BY MANLINESS -- THE WILLINGNESS AND ABILITY TO FIGHT.

In addition, Cicero seeks to free his young Roman readers of their fear of pain and death.

And that's another reason that he uses the word Fortitudo.

But it doesn't matter.

To both Aristotle and Cicero, Manliness is the Supreme Ethical Excellence, the Supreme Moral Virtue.

And to Cicero, in particular, all other virtues "have got the name 'virtue' from the single virtue which was found to outshine the rest" -- that is, from Manliness, Agenoria, Andreia, Areté, Virtus, the Willingness and Ability to Fight.

I've been saying that for the last seven years at least, and to me, as to Cicero, it's obvious.

All Moral Virtue, all Ethical Goodness, derives from Manliness.

Both in Latin, where virtue is virtus, and in ancient Greek, where it's αρετη.

And the source of the word areté is Ares, the God of Battle-Fight-War, as Liddell and Scott tell us :

And, Liddell and Scott add,

And, as in Latin, so in Greek :

All other virtues [aretai] "have got the name 'virtue' [areté] from the single Areté which was found to outshine the rest" -- that is, from Manliness, Agenoria, Andreia, Areté, Virtus, the Willingness and Ability to Fight.

In both Latin and Greek, all Virtue flows from Manliness and Fighting, all Virtue is an expression of Manliness and Fighting, all Virtue is rooted in Manliness and Fighting.

Bill Weintraub

September 25, 2020

EPILOGUE

XX. Will you, though you have seen boys in Lacedaemon, young men at Olympia, barbarians in the arena submitting to the heaviest blows and enduring them in silence -- will you, if some pain happen to give you a twitch, cry out like a woman and not endure resolutely and calmly?

"It is unbearable ; nature cannot put up with it."

Very well.

Boys endure from love of fame, others endure for shame's sake, many from fear, and yet are we afraid that nature cannot put up with what so many have endured in such a number of different places?

Nature in fact not only puts up with but even demands it ; for she offers nothing more excellent, nothing more desirable than honour [honestas], than renown [laus], than distinction [dignitas], than glory [decus]. By all this number of terms there is only one thing that I want to express, but I employ a number, in order to make my meaning as clear as possible.

What I want to say in fact is that far the best for man is that which is desirable in and for itself, has its source in virtue or rather is based on virtue, is of itself praiseworthy, and in fact I should prefer to describe it as the only rather than the highest good. Moreover, just as we use language like this in speaking of what is honourable [honestum], so we use the opposite in speaking of what is base [turpe] : there is nothing so revolting, nothing so despicable, nothing more unworthy of a human being.

~Cic. Tusc. 2.46, translated by JE King.

So :

At Rome, which is an Honour Society, what is honourable and morally noble [honestum], is opposed to what is dishonourable and morally base [turpe].

Just as, in ancient Greece, also an Honour Society, To Kalon is opposed to To Aischron -- so at Rome, Honestum is opposed to Turpe.

And says Cicero,

What that means is that to Cicero, Virtus -- Manliness -- is not merely the Highest Good but the Only Good.

That may sound hyperbolic to you, but when you read the Greeks and the Romans, it soon becomes obvious that that's what they believe.

That Manliness is not merely the Highest Good, but the Only Good, in the sense that, as Cicero says, all other Goods flow from it.

That's why Xenophon says to the Persians, at a moment of great peril, that the Greeks have no other good save Arms and Manhood :

Because, obviously, without Arms and Manhood, all other goods will be taken from you.

Manliness, then, is the Only Virtue.

And you can read more about what Xenophon said, and its significance, here.

Now :

When the issue of Honour and Pain first comes up, Cicero says to his young friend,

"To escape disgrace, crime and baseness, pain should not be rejected, but should rather be voluntarily invited, endured, and welcomed :"

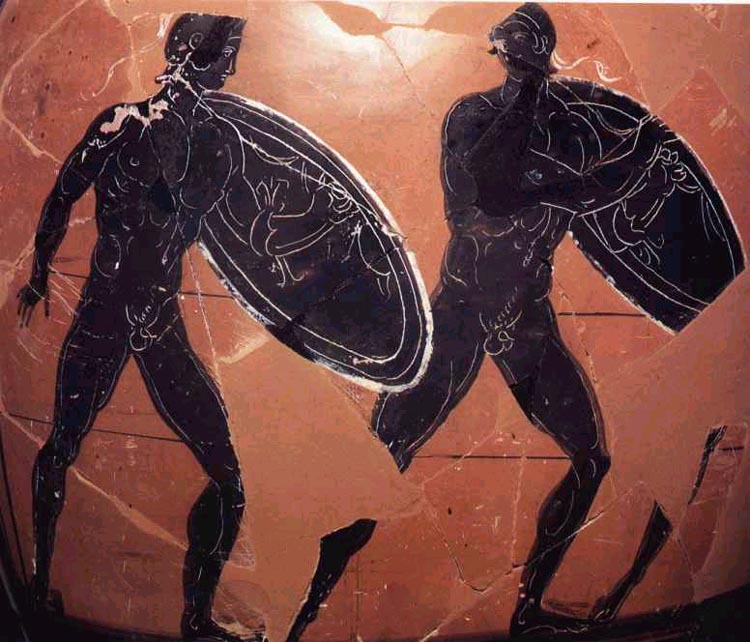

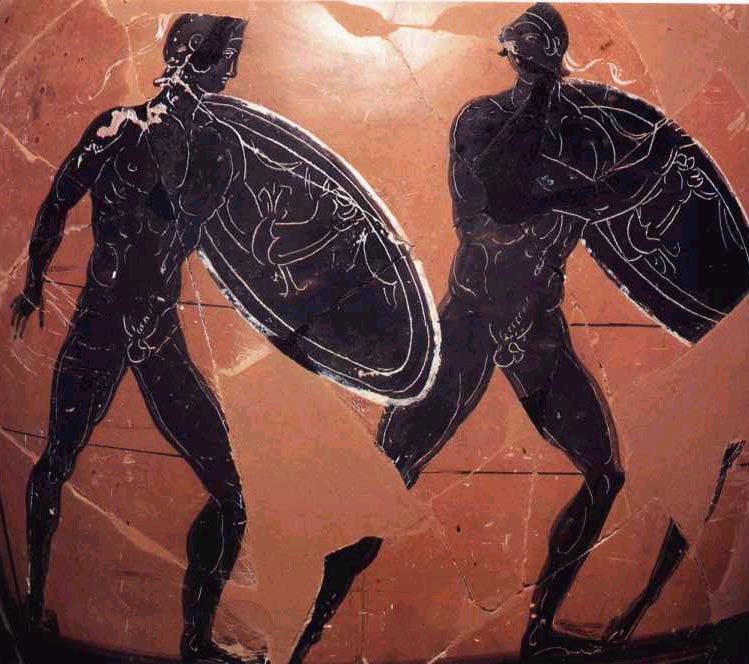

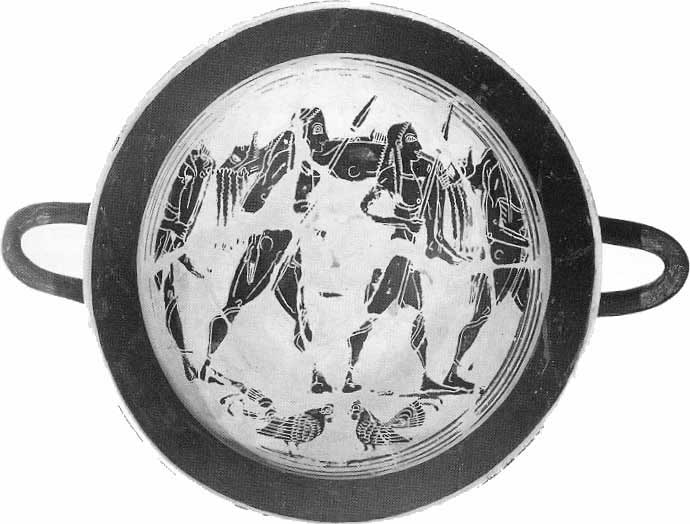

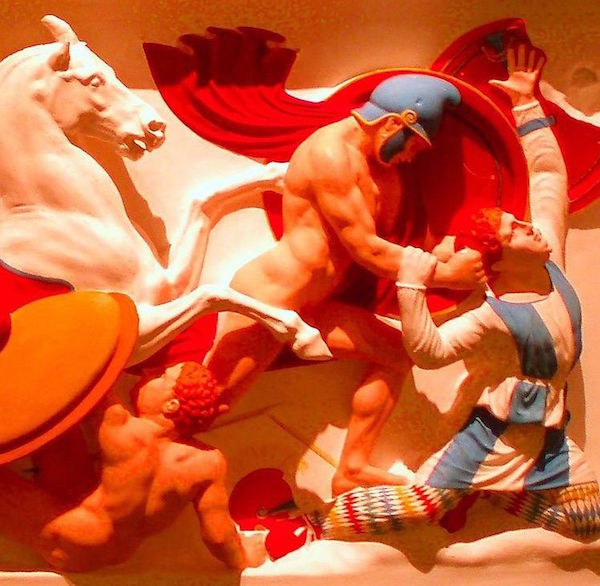

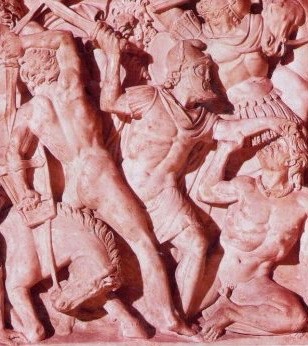

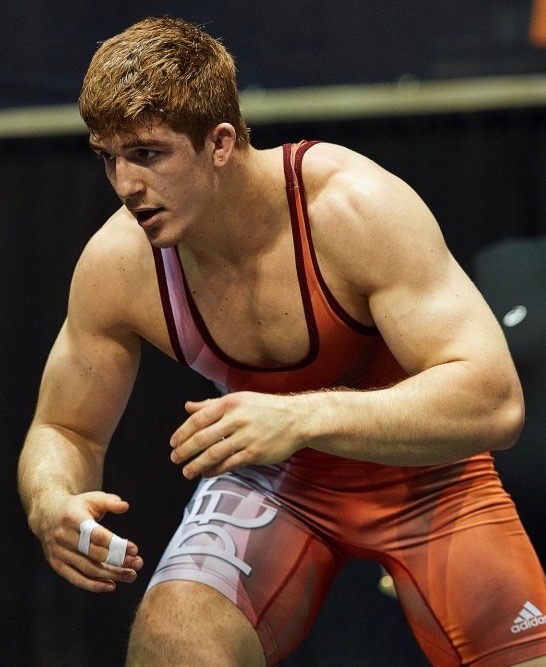

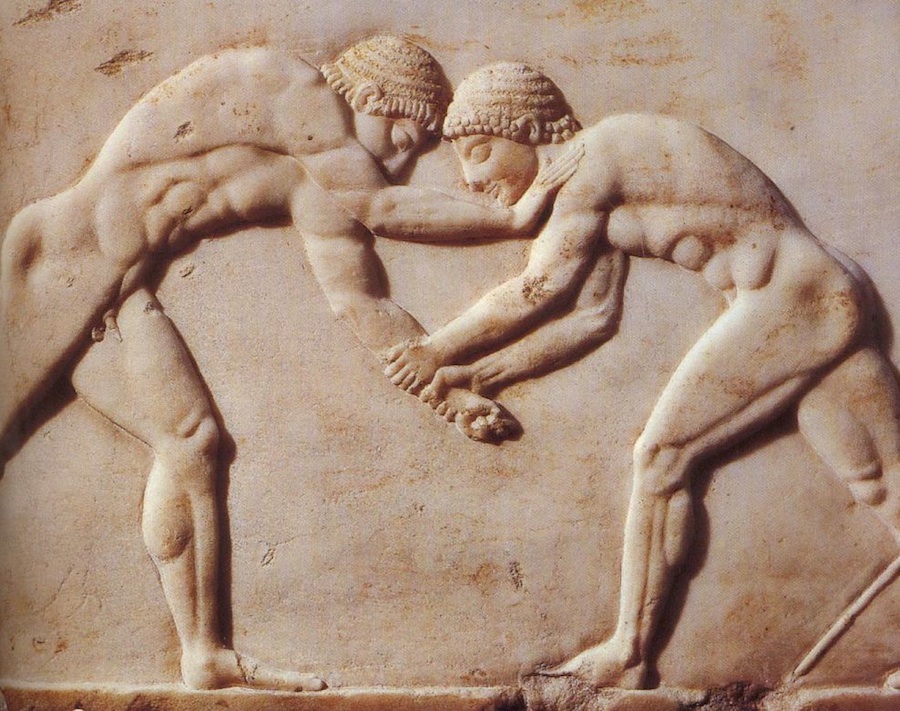

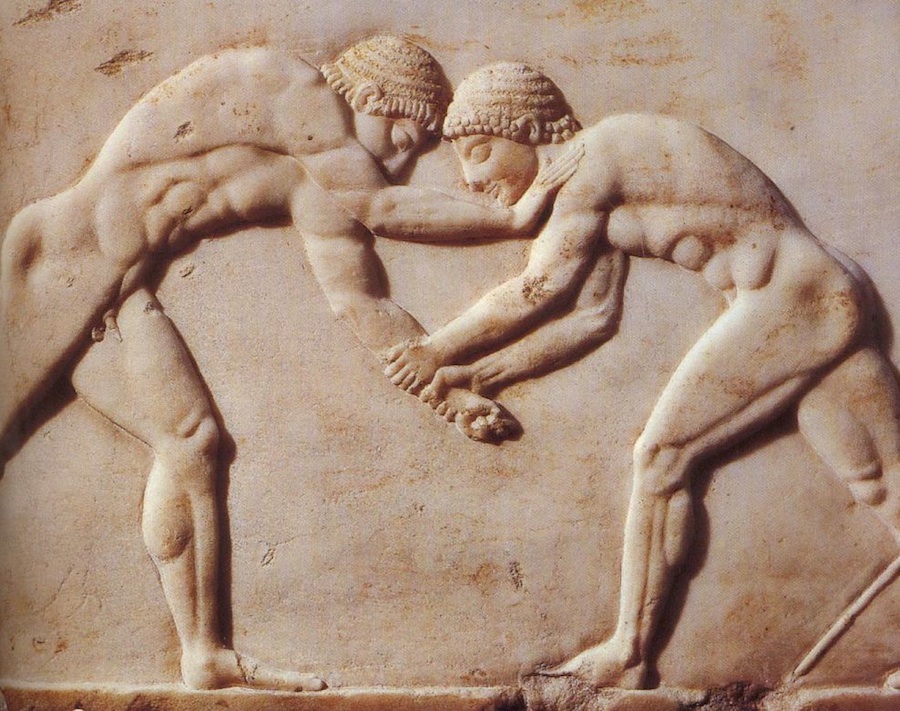

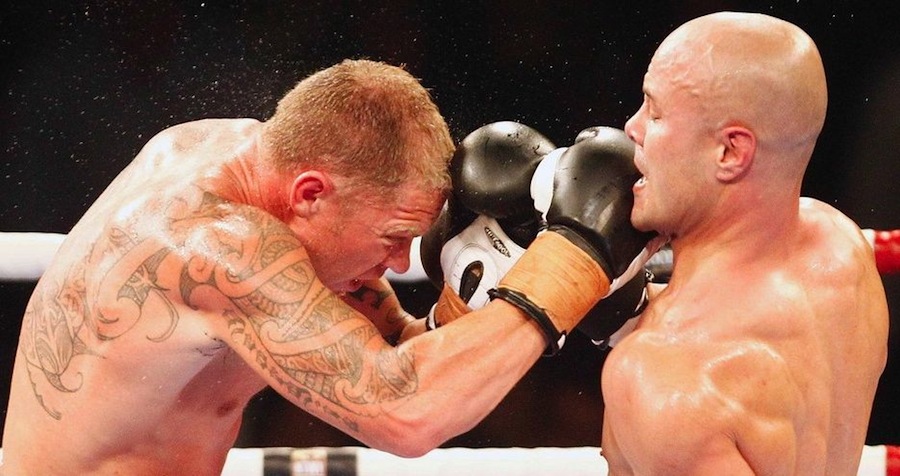

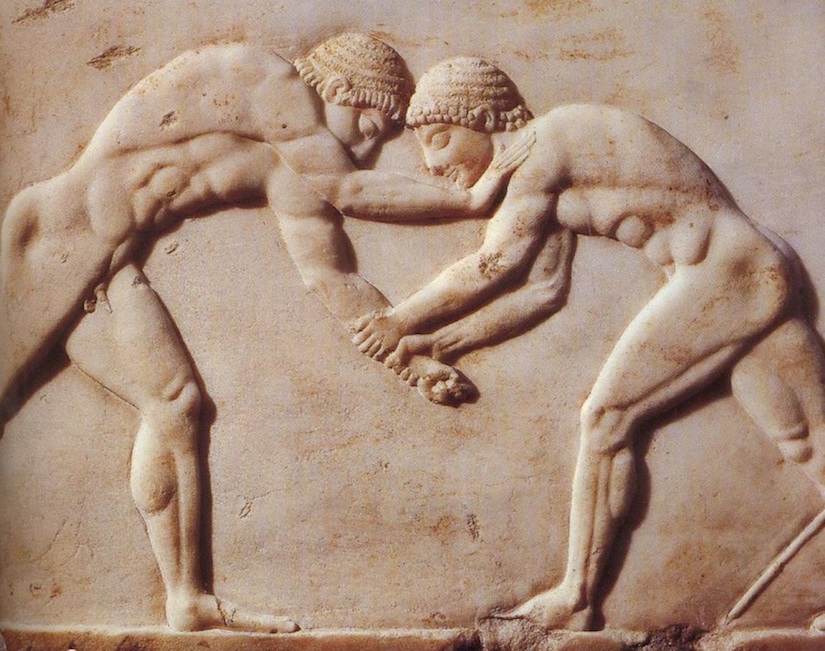

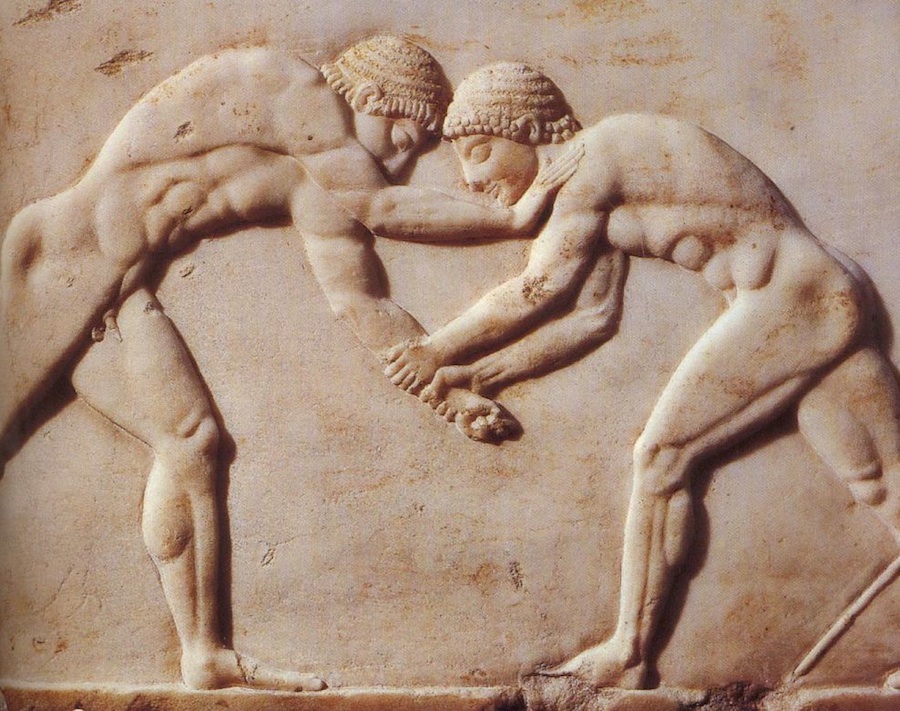

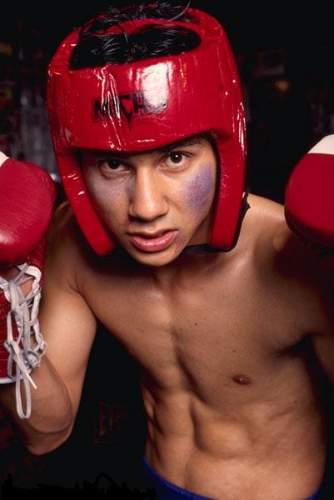

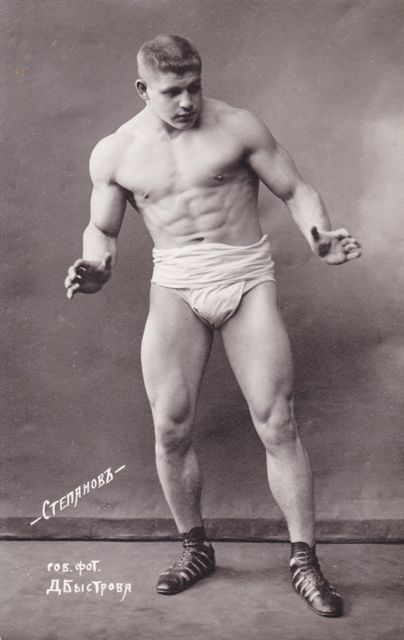

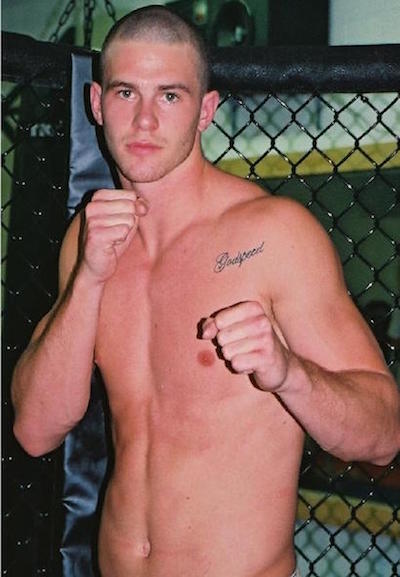

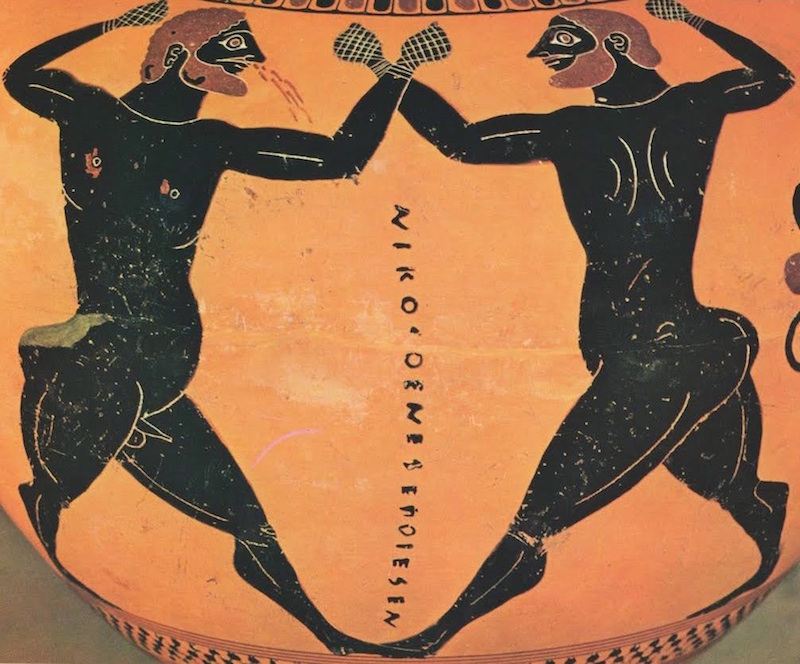

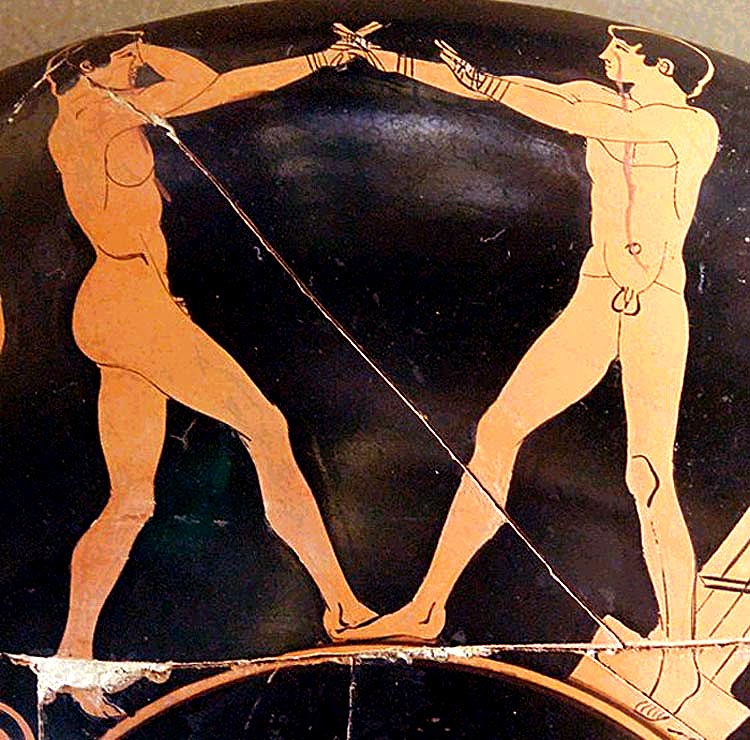

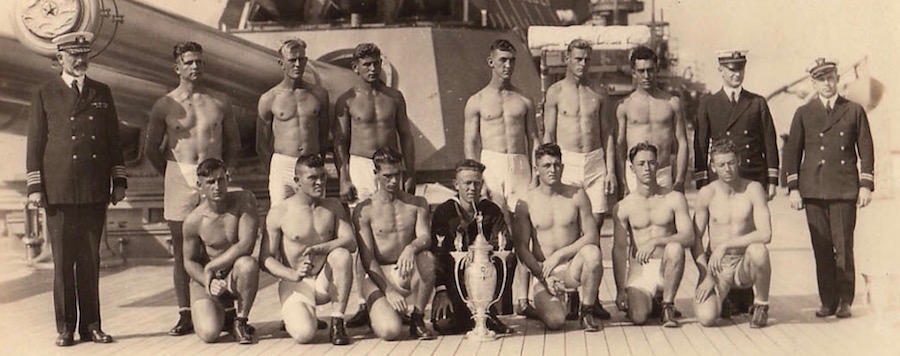

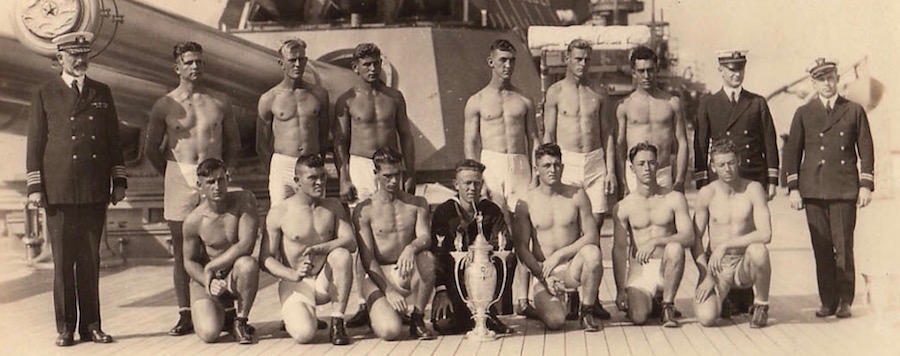

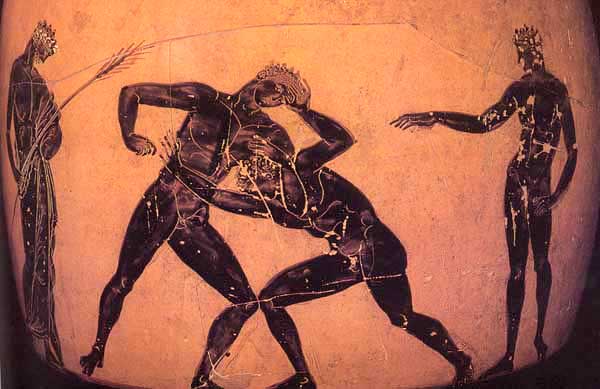

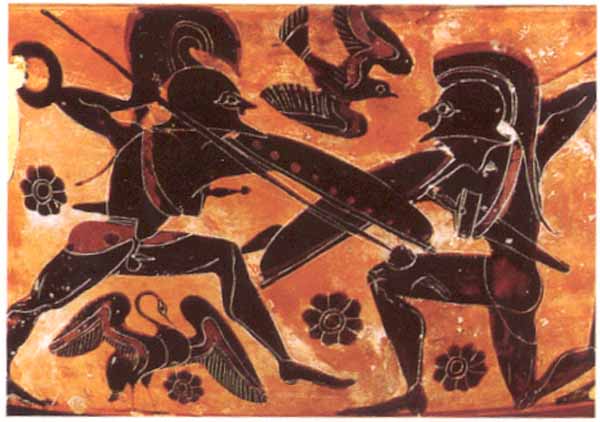

That's why, at the very beginning of this essay, I presented a series of pictures, including these :

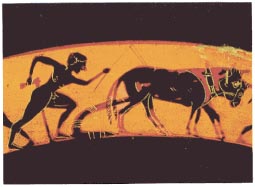

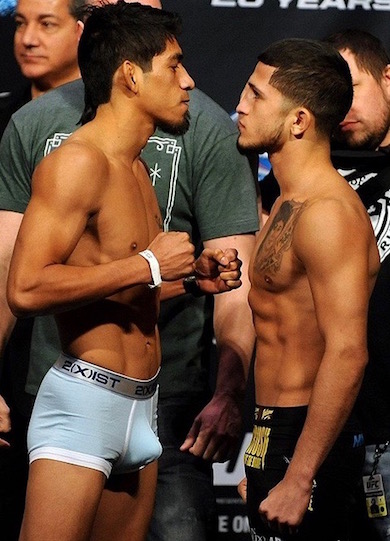

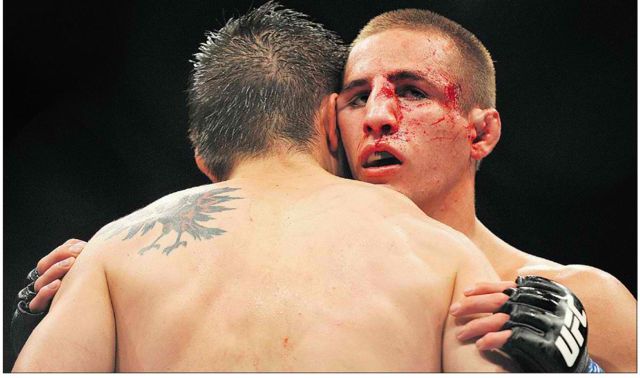

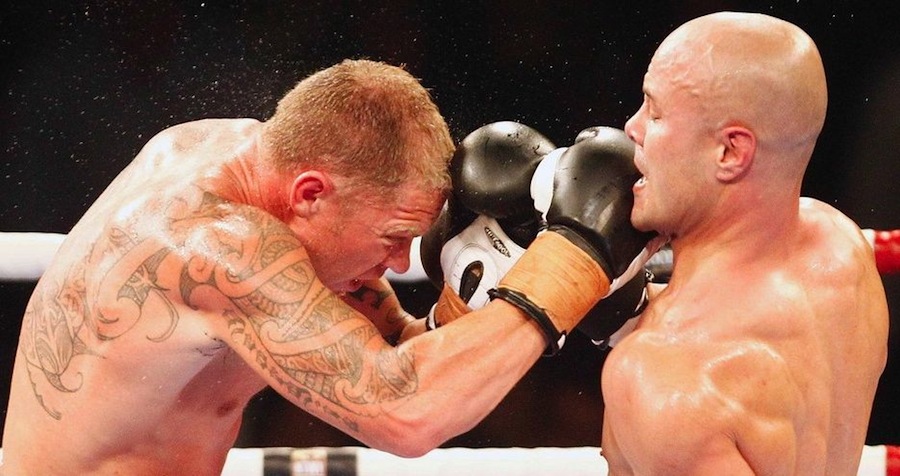

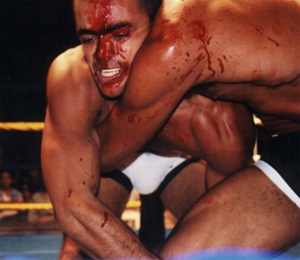

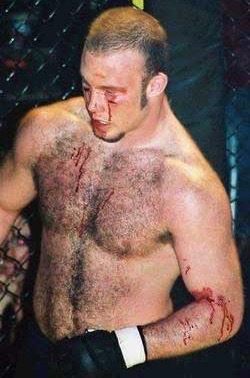

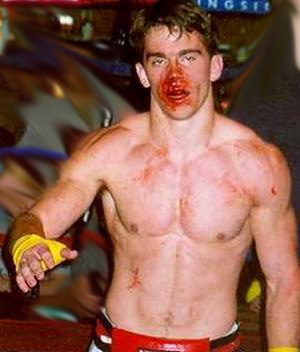

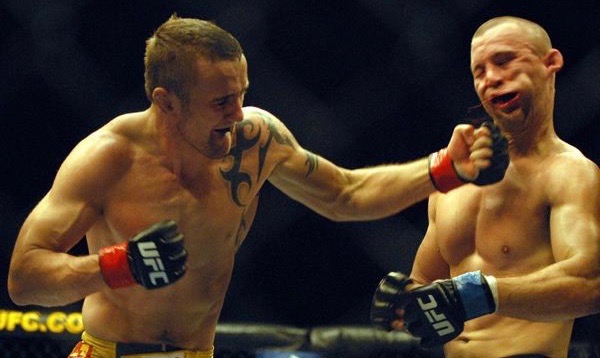

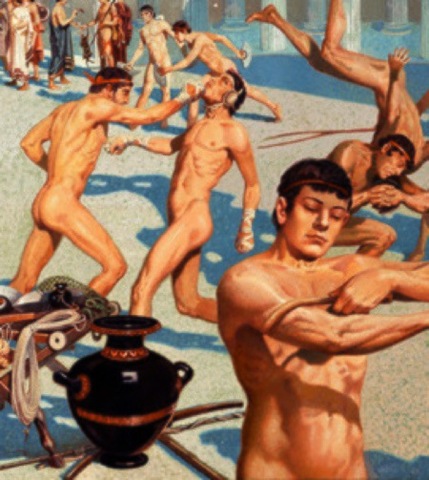

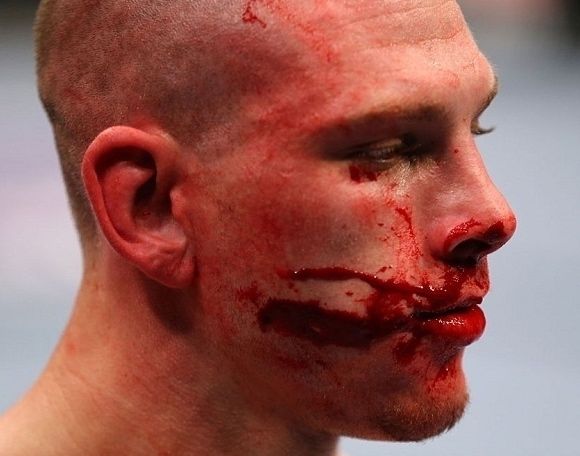

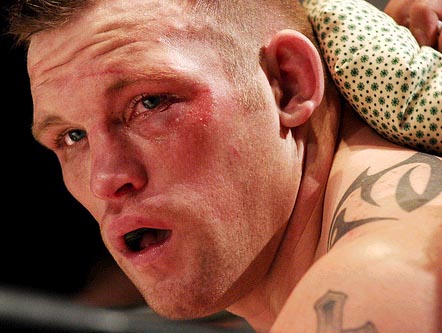

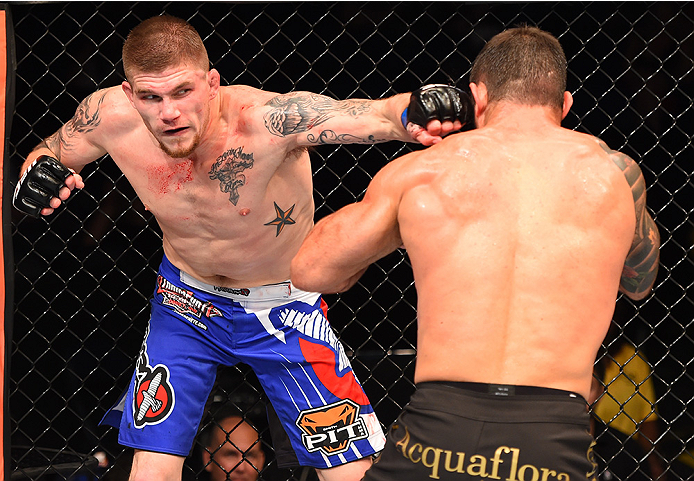

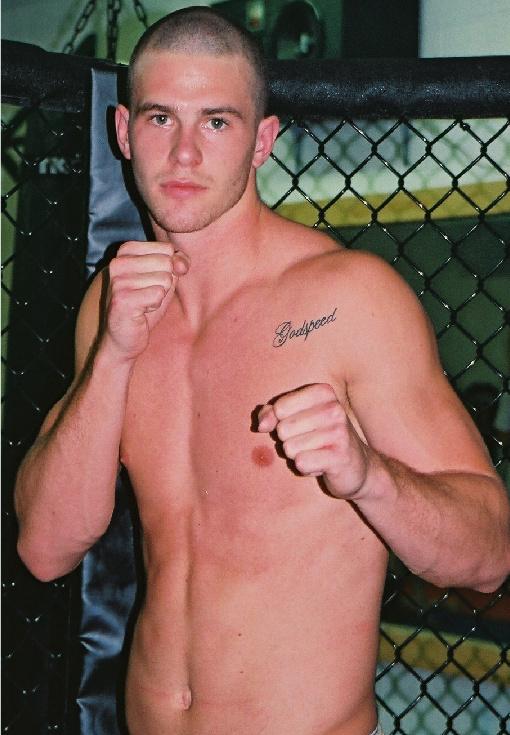

The Boxers and MMA Fighters in these photos have voluntarily invited, endured, and welcomed pain :

That's what Fighters do -- they invite, welcome, and endure pain.

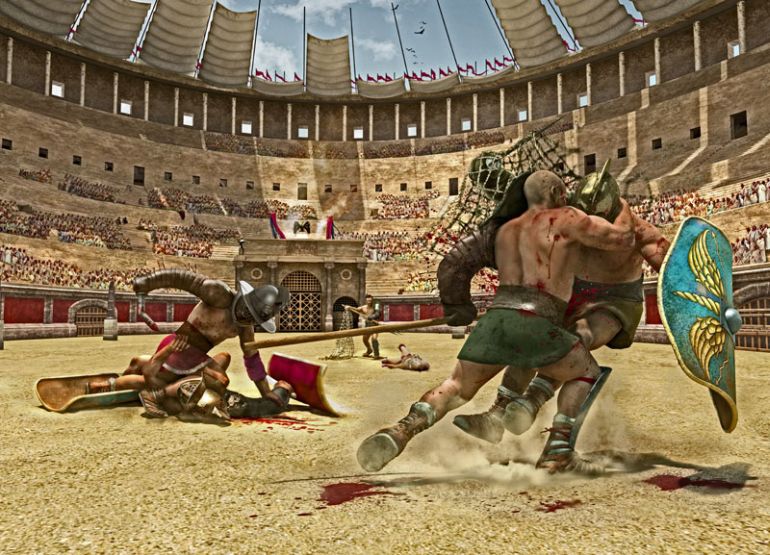

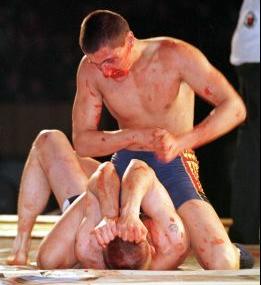

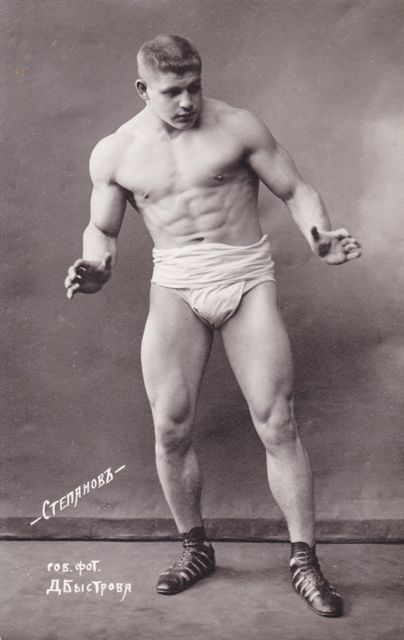

As do Gladiators, who, though they be ruined men or barbarians, nonetheless, through training and habit, have obtained the ability to scorn both pain and death :

They are, therefore, exemplars of what a Man should be :

So :

Here's a brief summary of what Cicero says :

CICERO :

Again, in both ancient Greek and Latin, the word commonly translated into English as "virtue," is either Areté -- which means Manly Excellence which is Manliness ;

or Virtus -- which also means Manliness -- the Willingness and Ability to Fight.

In the case of Latin, the word for virtue is Virtus -- which is why Cicero uses the word Fortitudo -- but he makes abundantly clear that Virtus as Manliness is the key Virtue, that it outshines all others and is the source of all others.

Aristotle, who precedes Cicero -- 384 - 322 BC vs 106 - 43 BC --

Aristotle, as we'll see, teaches that all Moral Virtue -- all Ethical Excellence -- is a matter of training and habit ;

and that therefore it is of supreme importance how a child is raised and what he is taught.

A child who's taught to stand up to blows face to face and to stand his ground -- will stand up to blows face to face and stand his ground -- both as a child and as a Man.

A child who isn't taught that -- will suffer from excessive fear, and effectively won't be a man.

He'll be an effeminate coward.

So -- we learn how to endure pain -- by enduring pain.

Fighting therefore confers Manliness.

While Manliness enables Fighting.

So, to both Aristotle and Cicero,

Training in Fight and Fighting itself confers Manliness -- the Willingness and Ability to Fight.

And Manliness in turn enables Fighting -- that is, because Manly Men scorn both pain and death, they're not afraid to Fight, but rather, as Cicero says, voluntarily welcome, endure, and invite, the pain of Fight into their lives.

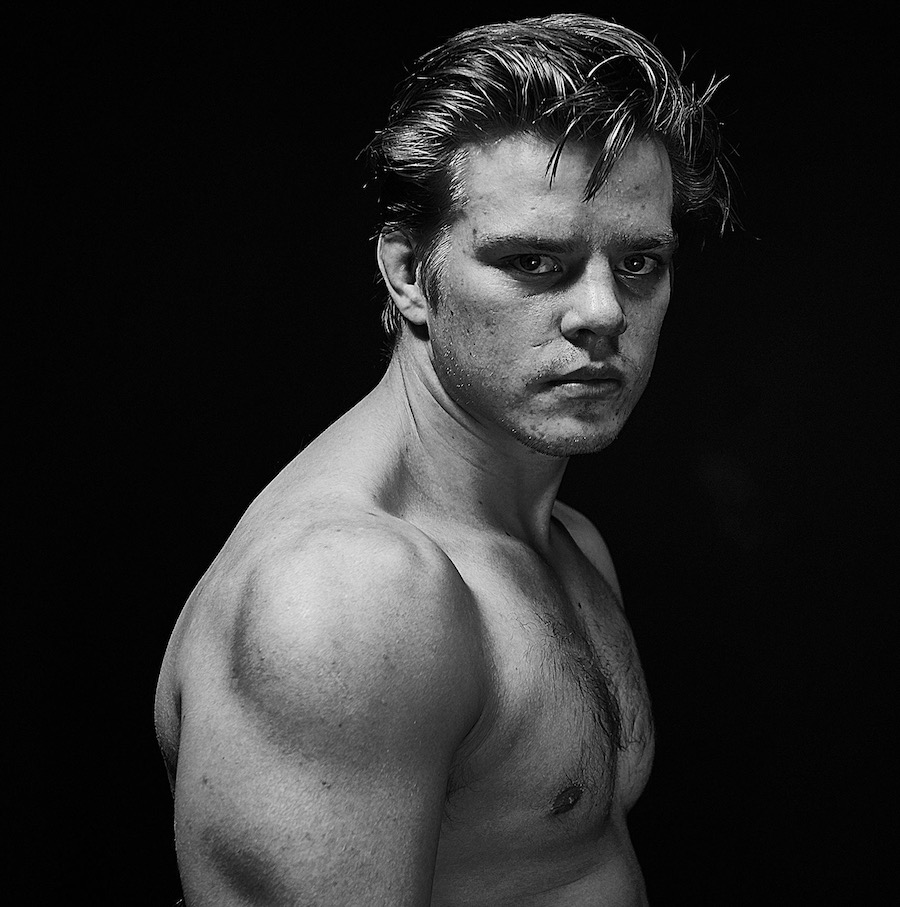

As Warrior NW did with the pain both of Wrestling and of MMA.

Manliness, then, like all the ethical excellences and moral virtues, is a matter of Training and Habit.

If a boy is trained to stand up to blows face to face, and therefore develops the habit of facing his opponent -- he becomes Manly.

A boy who isn't trained soon becomes excessively fearful of fight, of pain, and of death, he's afraid to face an opponent -- and becomes a cringing, effeminate, coward.

That's what happens.

Manliness, says Cicero, is the most important of the ethical excellences aka moral virtues.

It outshines all the other virtues, which are derived from Manliness -- Virtus -- because Virtus is derived from Vir.

In Latin, the word for Virtue -- Virtus -- derives from the word for Man and Fighter -- Vir.

In ancient Greek, the word for Virtue -- Areté -- derives from ARES -- the God of Battle-Fight-War.

In both cases, FIGHT is the sine qua non -- the "without which NOT" --

To both the Greeks and the Romans, you can NOT have VIRTUE -- without FIGHT.

This is from an email to NW :

One of the things you and I have often discussed is the definition of the Latin word Vir.

It means both Man and Fighter.

Not Man or Fighter, but Man and Fighter -- both, and simultaneously.

That matters, because it tells you how Roman society conceptualizes Men, and what Men are supposed to be.

And that conception has a real world impact.

Cicero, for example, a leader in Roman Society, is very clear that Virtus -- Manliness, which is the Willingness and Ability to Fight -- is by far the most important Virtue, that it outshines all the other virtues, and that all the other virtues emanate from it.

Because Cicero and his peers think that way, it influences, among other things, how children, and in particular boys, are raised.

If Vir means both Man and Fighter, and if the Supreme Virtue, Virtus, is Manliness, it becomes not merely important, but, as Aristotle says, of Supreme Importance, that boys are raised to become Fighters.

What that would mean for someone like yourself, NW, is that instead of having your first real experience of Fight when you were 20, you would have had it when you were about seven.

And that training in Fight would have continued into your adult life.

Fighting would have been a constant in your life.

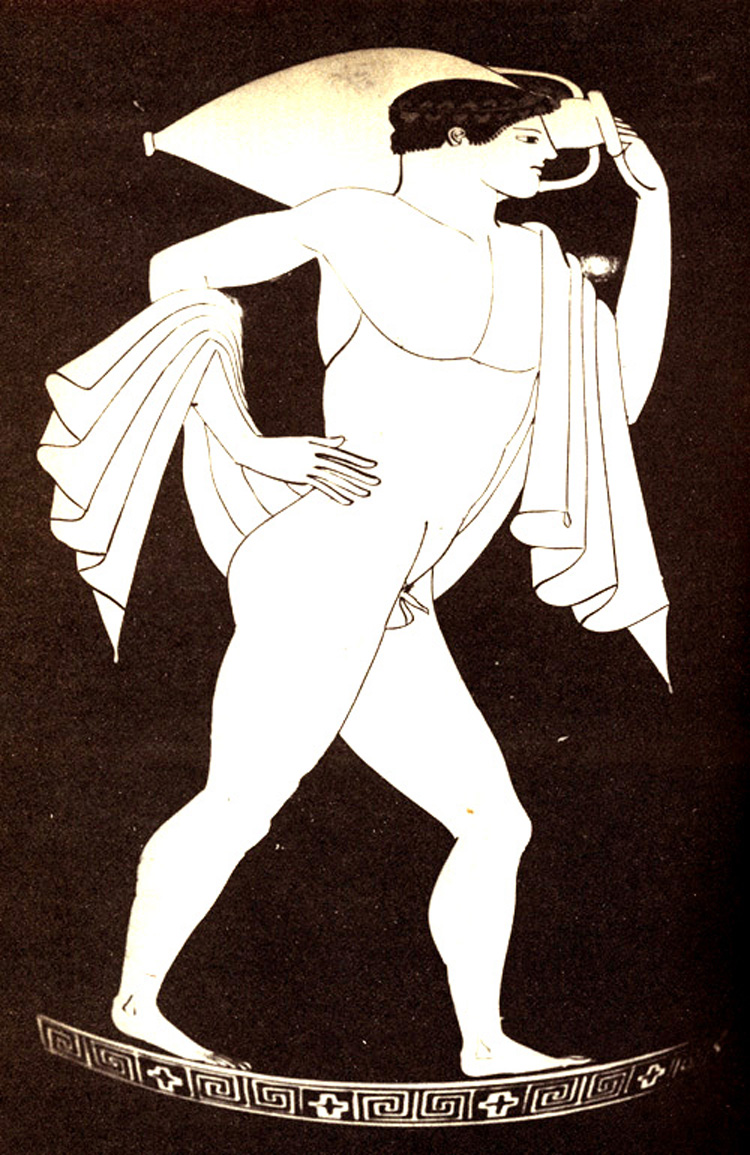

You would have been taken to see exhibitions of Nude Fight Free Fight -- Boxing, Wrestling, and Pankration --

and you would have also been taken to Munera -- Gladiator Displays.

From your schoolmasters, from your parents, from all significant adults, you would have heard constant exhortations to Fight.

Not to turn the other cheek, but to Fight.

Your childhood games would have been about Fighting -- including you and your best buddy taking turns hitting each other -- to see who could hit harder.

When the time came for you to choose a profession -- well, there were really only three professions for Men who came from good families :

War

Law

Administration

And before you could have a career in Law or Administration -- such as the Administration of a Province -- you had to serve in the Military.

You had to go to War.

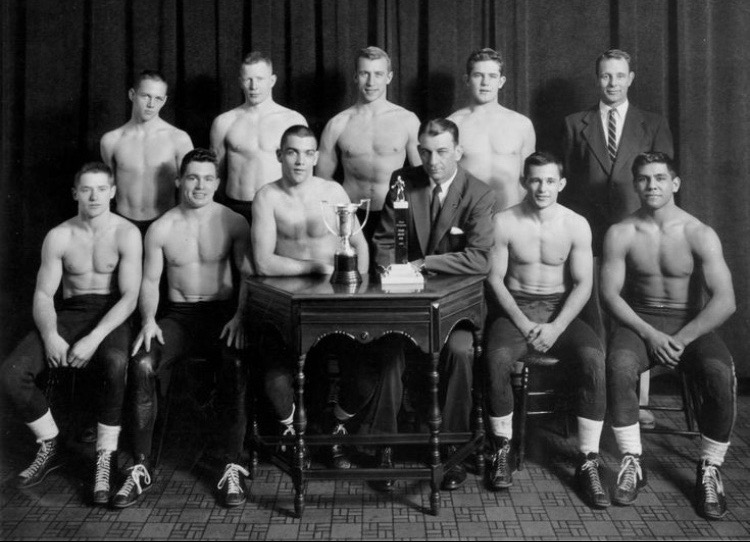

In the Military, you would have found yourself in the constant company of other Men -- Fighting Men, like yourself.

No women -- just Men, Fighting Men.

I think you would have enjoyed the experience.

And many similar experiences in your life.

Your life, in short, both as a Man and as a Man who's attracted to Aggression and the Beauty of Guys who Assert that Aggression -- would have been radically different.

And all because the word Vir means both Man and Fighter.

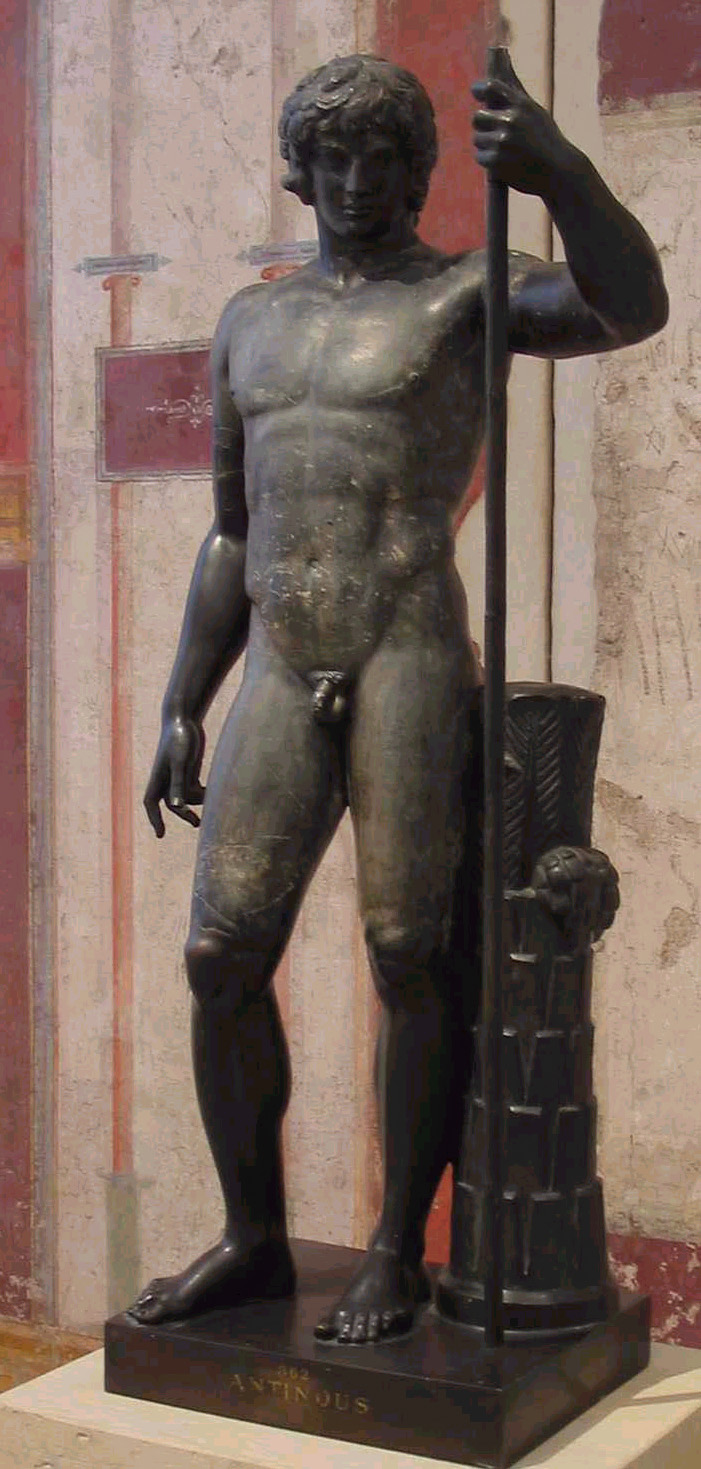

The Roman emperor Hadrian (117 - 138 AD) is one of the Great Men of History -- I discuss Hadrian and his beloved Antinous in The Deification of Antinous.

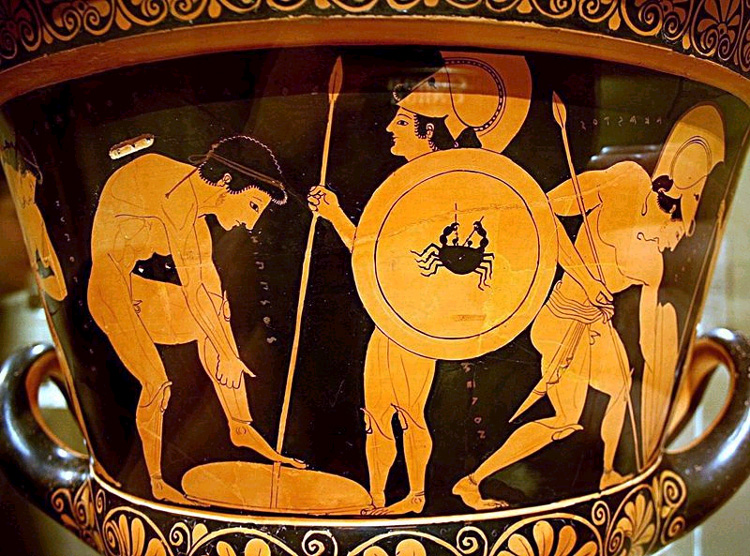

Hadrian, who led his legions into battle, trained as a Gladiator -- not so as to Fight in the arena, but to better Fight on the field of Battle.

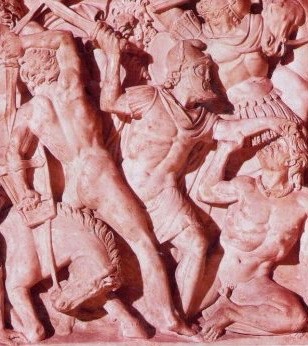

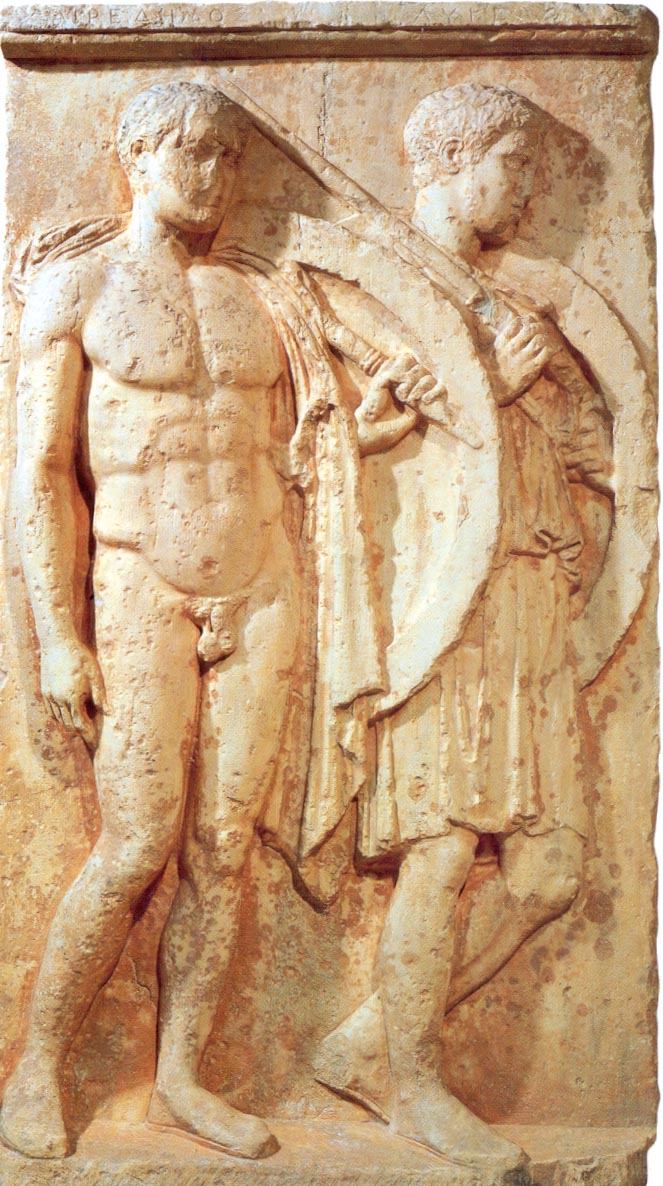

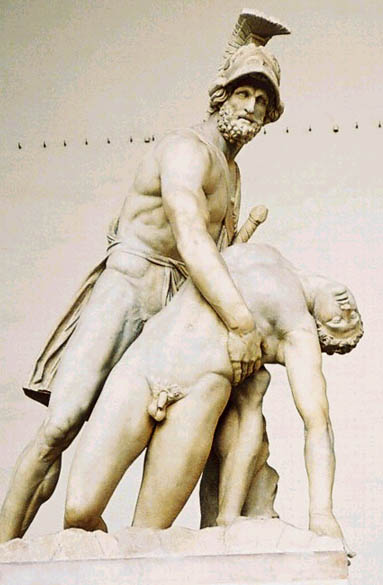

This is a statue of Hadrian which he sanctioned :

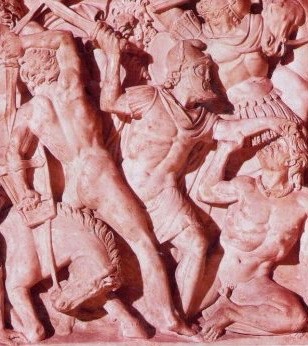

In this statue, the Fighting Gladiators Instantiate Fighting Manhood -- the Willingness and Ability to Fight ; while Hadrian, who, again, trained as a Gladiator, was an ardent PhilHellene -- Lover of Greek Culture --, and had a Beloved named Antinous, personifies the Roman Warrior God Mars.

And this is a statue of his lover Antinous, also in the guise of the God Mars -- the War God :

The Romans began their calendar with the month we call March, which was sacred to Mars, the father of Romulus and Remus and thus the primogenitor of the Roman people.

That's how important Fighting was to the Romans.

Let's take one more look at the statue of Hadrian with the Nude Fighting Gladiators on his breastplate :

Ancient Greek and Roman Men had not been effeminized, or heterosexualized -- or, of course, christianized -- that is to say, de-wild-ed, un-savaged, tamed, and unrelentingly domesticated -- in the way males in our time have been.

Put differently, the Greeks and Romans were Manly to an extent that most of you would have a very hard time conceptualizing or just comprehending.

They were neither tame nor domesticated.

They were Men -- wild and free.

And that's true of the many Warriors and Warriordoms they Fought -- Kelts, Teutons, Picts, Galatians, Macedonians, etc.

They were all Men -- wild and free.

For example, there's a Latin word -- Ferocitas ; it means wildness, fierceness, courage, spirit, intrepidity ; fierceness, barbarity, ferocity

And it derives from Ferox : wild, bold, courageous, warlike, spirited, brave, gallant, fierce

All of which is to say -- Manly.

Fighterly.

Willing and Able to Fight -- Ferociously.

So :

To the Greeks, and the Romans, the words Masculinity, Manliness, Manhood, Manly Spirit, Manly Excellence, Manly Goodness, and Manly Virtue -- always refer to Fighting -- Fighting Masculinity, Fighting Manliness, Fighting Manhood, etc.

And we can see that in Greek Warrior Names, which are aggressive and combative, and often make reference to violence and brute force.

Polybiadas, for example, a Spartan name, means Son of [das] Mighty [poly] Violent Force [bia] ;

While Alkibiades, an Athenian name, means Son of [des] Valiant [alkimos] Violent Force [bia].

And we're soon going to look in depth at the work of Aristotle, the pupil of Plato and tutor of Alexander the Great, and Aristotle's discussion of the Ethical Supremacy of the Moral Virtue of Manliness -- that is, of the Willingness and Ability to Fight.

So let's consider Aristotle's name, which in ancient Greek is Aristoteles.

The first part, Aristos -- Most Manly --, derives from Lord Ares -- as Liddell and Scott so helpfully tell us :

From the same root [ΑΡΗΣ -- ARES] come areté / areta [Excellence], ari-, areion [better -- stronger, braver, more Manly], aristos [best -- strongest, bravest, most Manly], the first notion of goodness being that of manhood, bravery in war; cf. Lat. virtus.

~Αρης, defined by Liddell and Scott.

And, Liddell and Scott add,

~Αρετα, defined by Liddell and Scott.

Notice the emphasis on "manly qualities, manhood, valour, prowess (like Lat. virtus, from vir)."

Manly qualities are qualities which define the Willingness -- Valour -- and Ability -- Prowess -- to Fight.

Aristo, then, means Most Manly -- while Teles means both Purpose -- and Perfection.

Aristoteles is He who is Most Manly -- that is, Most Willing and Able to Fight -- in Purpose and Perfection.

Fighting.

My work is about Fighting.

Violent, Brutal, Bloody --

Fighting.

And it's always been about Fighting -- all my life, my entire life.

It's been about Fighting.

My life and my work have been about Fighting.

My sites and my work are about Fighting.

Including my work about Phallus-Against-Phallus.

That too is about Fighting and has always been.

So :

As I conceived of cock-rub as an adolescent, it was that me and the other boy would Fight, and that at the same time our cocks -- our hard cocks -- would Fight each other.

Fight.

Violently and Brutally.

That's how I conceived of it -- as a youth -- and that's how I still conceive of it -- as a Man.

As a combination, a combining, of Phallus and Fighting.

A combining of Phallus and Fighting in which the Phallus -- my Phallus, the Man's Phallus -- would become, like all other elements of the Man's body, subordinate to the overwhelming and indeed inescapable need of his Fighting Manhood --

To FIGHT :

Me and the other boy would Fight, and at the same time So :

Just as my fists would Fight my foe's fists, my arms his arms, my legs his legs, my pecs his pecs -- so would our hard cocks Fight each other.

And again, that Fight would be an impossible-to-deny expression of each agonists' Fighting Manhood, his Fighting Manhood, not his genital manhood -- for as I conceived of this Fight as a boy and as I've conceived of it as a Man, it's not about sex.

It's about Fighting and Fighting Manhood.

Yes, there's a passage through rage to love, yes there results a Harmony of Parts Naturally at War.

But before there can be Harmony, there must be Discord, there must be War.

The effeminized guys who write to me want an amorous Manly harmony without its necessary precursors of Struggle and Strife, Contention and Conflict, Discord and Battle and Fight ; but that's not possible.

Because within the male-male matrix, the absence, the lack, the want, of Battle-Fight-War -- of Fighting -- of Fighting which confers Manliness --

The absence of that Fighting which confers Manliness -- can lead to only one thing, and that is UN-manliness, which is and has always been -- analism.

That is, anal, promiscuity, and effeminacy.

History tells us that within a culture, you can have Manliness or UN-manliness -- but you can't have both.

In the sense of both being normative.

In our culture, which is hedonist and ethically nihilist, analism is normative, and Manly Love -- that is, an Exclusive and Faithful Love between Two Men, each of whom is Willing and Able to Fight -- Love between Warriors, Love between Combatants, Love between Fighters, Love between Men --

Manly Love -- is deviant.

In ancient culture, which is Warrior Culture, Manly Love is normative, and analism is deviant.

~ Lucian, translated by Sweet.

Cicero witnessed that Fighting.

This is his description as it appears in The Tusculan Disputations.

Cicero :

Pain seems to be the most active antagonist of virtue ; it points its fiery darts, it threatens to undermine Fortitude [Manliness], Greatness of Soul and Patience. Will Virtue [Virtus] then have to give way to pain, will the happy life of the wise and steadfast Man yield to it?

What degradation, Great Gods of Heaven!

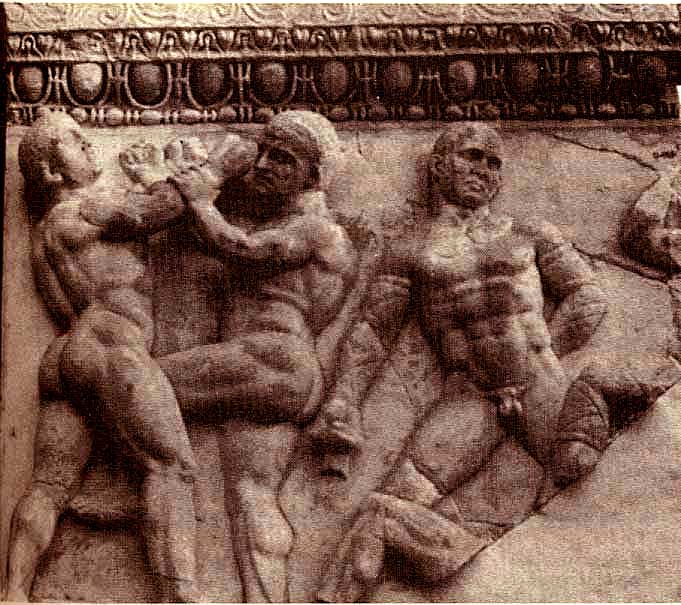

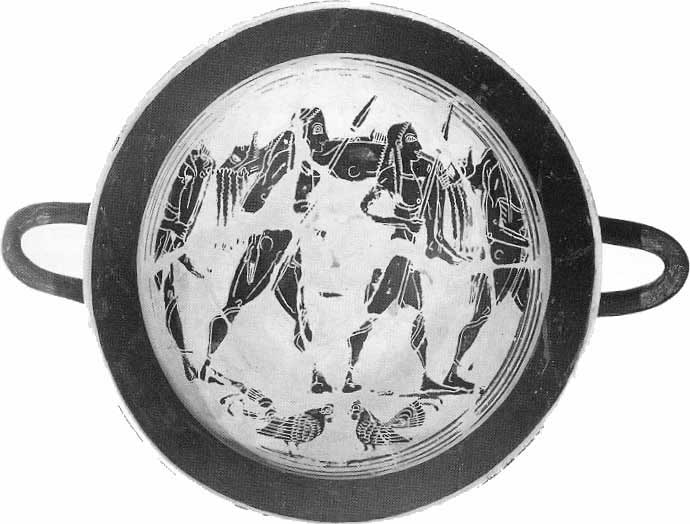

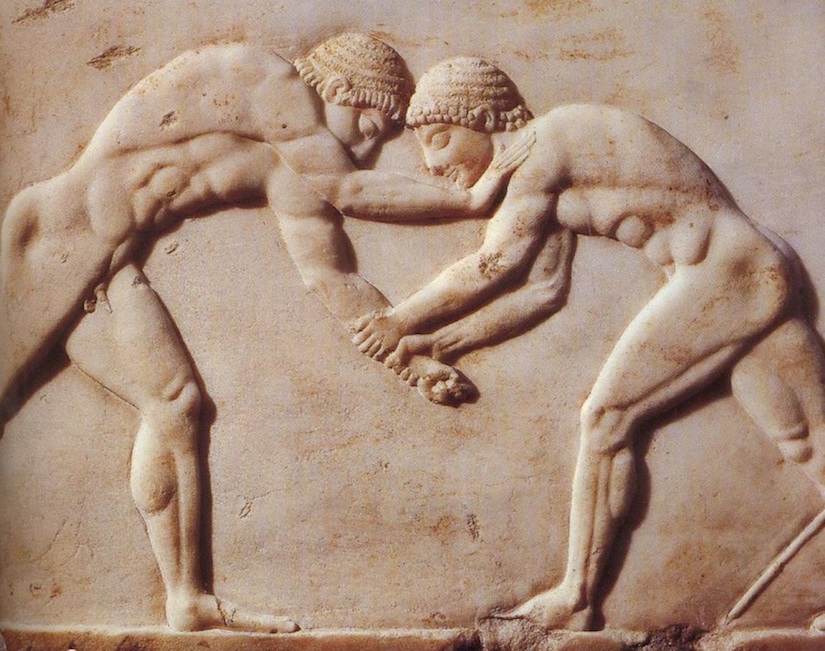

Spartan boys utter no cry when their bodies are mangled with painful blows ; I have seen with my own eyes troops of youngsters in Lakedaimon Fighting with inconceivable obstinacy, using fists and feet and nails and even teeth to the point of losing their lives rather than admit defeat.

Fighting.

My work is about Fighting.

Violent, Brutal, Bloody --

Fighting.

And as you just read in Cicero, the ancient world was about Fighting.

Violent, Brutal, Bloody --

Fighting.

Ancient Men were constantly immersed in Fighting -- and Manliness.

Biologically, Culturally, and Spiritually, Fighting and Manliness reigned Supreme.

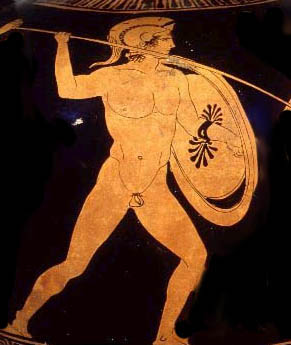

Which is why when a Greek, a Fighting Man, refers to his Phallus as his Andreia, his Manhood, he's thinking of it as his Fighting Manhood, and without question, therefore, as a Weapon, a Manly Weapon, a Fighter's Weapon, an instrument of Battle-Fight-War -- a Spear, a Sword, a Club.

To be used Combatively, and Aggressively -- Roughly, and Brutally.

Roughly.

And Brutally.

For example, the great classicist and poet Robert Graves, in his encyclopedic The Greek Myths, points out that when a God like Apollo or Zeus desires a mortal woman, he doesn't chat her up or bring her flowers -- he simply takes her -- "roughly."

Roughly.

The ancient Greeks thought that women were mere receptacles for Man's seed.

Nor would they concede that the female body contributed physical characteristics to the baby which was born from it.

As the God Apollo says in Aeschylus' Eumenides, woman is the soil in which Man plants his seed :

The mother is no parent of that which is called

~translated by Lattimore

Apollo goes on to say that proof there can be a father without a mother is Athene, daughter of Olympian Zeus.

This belief is persistent throughout antiquity.

Indeed, 500 years later, a Greek writer refers to the woman's "womb [as] fertile ground for ploughing, as it were, and sowing."

To the Greek, the Phallus is analagous to an Iron Warrior Implement, a Weapon -- Hard and Un-yielding.

And the same with a Roman speaking of his Warrior Membrum Virile -- the Manly Member, always Willing and Able to Fight, Manful, Worthy of a Man, Brave, Bold, and Imbued with Fighting Spirit.

When the Greek intellectual Plutarch wrote, in Greek, an essay on Philostorgia -- that is, tender love and warm affection -- towards one's offspring, the Roman writer Fronto said that it would be impossible to translate even the title of the essay into Latin, because there was no such quality as philostorgia, that is, tender love or warm affection, at Rome -- and consequently no word for it.

Which means that ancient Greek and Roman Men were unlikely to think of their Phalluses as organs to be used tenderly, or affectionately, or lovingly.

Again, to both the Greek and the Roman, the Phallus is analogous to an Iron or Steel Warrior Implement, a Weapon, a Club, a Sword, a Spear -- Hard and Un-yielding -- and to be used as such.

Now :

I don't expect you guys to understand or believe what I'm saying, and that's because of your abysmal ignorance, the consequence of your never-ending refusal to do that reading in ancient literature which would enlighten you.

You don't understand, for example, what happened when an ancient city was taken by the enemy and sacked.

But what happened is that the defending warriors were killed, and their women were raped.

Repeatedly, in many instances.

While groups of soldiers stood around watching -- and waiting for their turn.

A woman of high birth, like Hektor's wife Andromache, might be taken by a high-ranking enemy, such as Achilles' son Neoptolemos, and kept for years as a sex -- and baby-making -- slave.

During the rapes and afterwards, the city was pillaged -- looted.

Ancient soldiers, both Greek and Roman, regarded the rapes and loot as essential -- they were perks, or if you prefer, entitlements, and a commander who tried to prevent them from raping and pillaging -- would face a violent and well-armed mutiny during which he'd likely be killed.

During the Roman civil wars, Brutus, "the noblest Roman of them all," who had written a book on Virtus -- a book which is now lost to us -- was forced by his legionaries to promise them that the Peloponnesus -- about half of the Greek peninsula -- would, in victory, be theirs to sack -- to rape and pillage.

Quite a promise.

I said that a high-born woman like Andromache might be kept for years as a sex-slave.

So were many of the other women, but they were just common prostitutes, owned by a pimp.

We get an idea of just how many from Plutarch's essay titled "On Being a Busybody" :

Inquisitiveness, in fact, is indicative of incontinence no less than is adultery, and in addition, it is indicative of terrible folly and fatuity. For to pass by so many women who are public property open to all and then to be drawn toward a woman who is kept under lock and key and is expensive, and often, if it so happens, quite ugly, is the very height of madness and insanity.

~Plut. De Curiositate 9, translated by Helmbold.

[J]ust as at Rome[, in the marketplace,] there are some who take no account of paintings or statues or even, by Zeus, of the beauty of the boys and women for sale, but haunt the monster-market, examining those who have no calves, or are weasel-armed [have exceptionally short arms], or have three eyes, or ostrich-heads, and searching to learn whether there has been born some "Commingled shape and misformed prodigy" . . .

~Plut. De Curiositate 10, translated by Helmbold.

Basically, the ancient Greek and Roman world, and particularly, of course, the Roman Empire, was awash in slaves.

Many, many women were sold into sex slavery.

As could be beautiful boys as well -- something the Romans rarely admitted to, but Plutarch is quick to point out.

Which means, again, that ancient Greek and Roman Men were unlikely to think of their Phalluses as organs to be used tenderly, or affectionately, or lovingly.

Again, to both the Greek and the Roman, the Phallus is a Warrior Implement, a Weapon, a Club, a Sword, a Spear -- Hard and Un-yielding -- and to be used as such.

And that's how you need to think of it too.

Not as an effeminized and deformed sex toy --

But as a Warrior Implement, a Weapon, a Club, a Sword, a Spear -- Hard and Un-yielding -- and to be used as such.

Read the Iliad -- not one of you has -- and then try to tell me that Achilleus thinks of his Phallus the way you do.

Of course he doesn't.

He thinks of it the way the Greeks do -- the Warrior Greeks, the Homeric Greeks.

And what's needed is not that Achilleus becomes you -- but that you become Achilleus.

That's the point of the Epic.

And the Phallus.

Plato says of the Phallus that it's "disobedient and self-willed, like a creature deaf to reason, and it attempts to conquer all in its raging lusts."

~Plat. Tim. 91b, translated by Bury and myself.

Phallus seeks to Conquer Phallus.

Cock seeks to Conquer Cock.

And Plato understands that the Nature of Man -- his innately Combative and Aggressive Nature -- leads inevitably to Warrior Contest which leads to Warrior Conquest.

Just as he understands that the Nature of Phallus -- which in its raging lust attempts to Conquer All -- leads inevitably to Phallic Contest which leads to Phallic Conquest :

Man Seeks to Conquer Man.

And Phallus to Conquer Phallus.

Boners and Fists.

The problem you guys have is that you get boners, but you're afraid to make a fist.

Nevertheless, Boners and Fists is what Man2Man is about.

And it's Violent and Brutal.

So :

My work is about Fighters.

My work is about Fighting.

My work is about Fighters Fighting

In my work, the contest of phallus against phallus is always presented as a combative and aggressive act, and is always accompanied by the equally combative and aggressive Fighting of arm against arm, leg against leg, fist against fist.

My work is about Fighters Fighting -- Man Against Man , Phallus Against Phallus.

There are more than 1200 pages in my sites.

Almost all of them have pictures of Fighters Fighting.

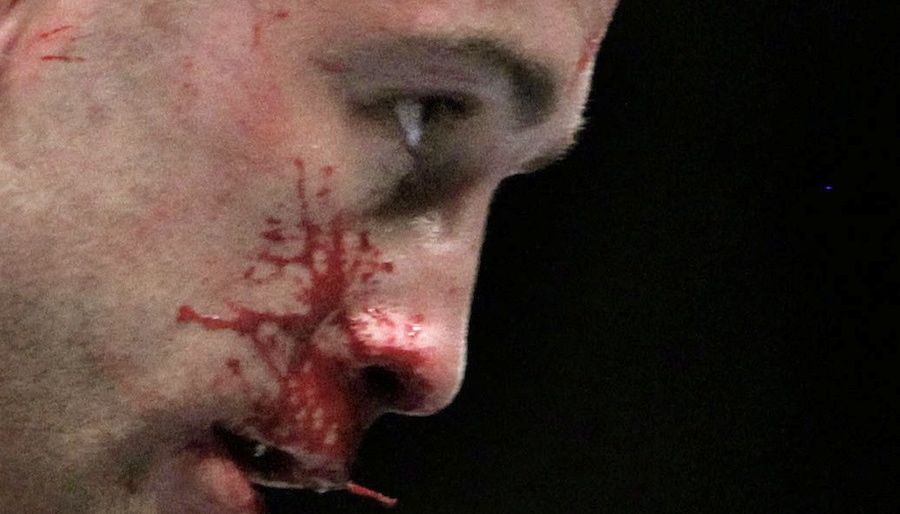

That Fighting is unmistakably Violent, often Brutal, and frequently Bloody.

Again, it is unmistakably so.

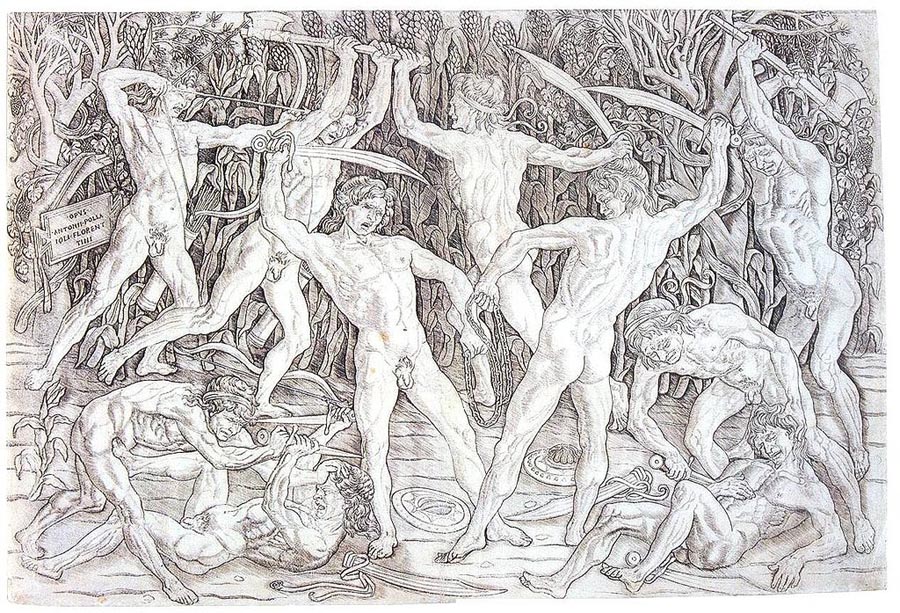

Throughout my work and my sites there appear Manly images, Martial images of Fight-Battle-Combat-Strife-Struggle-War, images of Fierce Fighting Manhood and Pugnaciously Perfect Manliness, and most of those Masculinist, Phallo-centric, and implicitly Pagan images are Bloody, Violent, and Brutal -- as Man2Man Fighting is and should be :

That's Fighting.

Bloody, Brutal, and Violent.

That's Fighting.

Bloody, Brutal, and Violent.

And that's how I think of Phallus-Against-Phallus and have thought of it since childhood :

Once aroused, the Phallus is Brutal and Violent, just as Brutal and Violent as Fighting Men themselves, and like those Fighting Men, it seeks, in its raging lusts, to Conquer all.

And as such, it's an instrument and expression of Fighting Manhood, and not of anything else.

My work and my sites are about Fighting.

Not just somewhat about or 75% about or even 95%.

My work and my sites are about Fighting.

Including that part of my work and my sites which is about Phallus-Against-Phallus.

Phallus-Against-Phallus is about Fighting.

Just as Man Fights Against Man ;

So Phallus Fights Against Phallus.

Phallus-Against-Phallus is an expression of Fighting Manhood.

That's the way I conceptualized it as a boy, and that's the way I've conceptualized it as a Man.

Phallus-Against-Phallus is an expression of Fighting Manhood.

Boy would Fight Boy, Phallus would Fight Phallus.

And that Fighting would be Violent and Brutal.

Specifically :

The Fighting of Boy Against Boy would be Violent ;

And the Fighting of Phallus Against Phallus would be Brutal.

That was my conception.

And it hasn't changed.

Not one iota.

That's why there's so much discussion of Fight, Fights, and Fighting in my work.

And so many pictures of Fights and Fighters -- Bloody, Violent, and Brutal -- on my sites.

Again, those pictures of Fights and Fighters -- Bloody, Violent, and Brutal -- are on my sites because my work and my sites are about Fighting.

And those of you who don't like Fighting, or who don't approve of Fighting's Brutality and Violence --

Shouldn't be here.

You'd be happier somewhere else.

There are, after all, a gazillion sites for feminists and for their "gay male" admirers and supporters.

For it's as my foreign friend says :

The heterosexual society cares only for women. It sees men only as a problematic group that comes in the way of what is called women's rights.

Gay males are among the most ardent supporters of heterosexualization. They represent the dust bin created by the heterosexualised society to contain the mutilated / negativised remnants of male-male sex that survives after the intense oppression of them in the mainstream...

Gay males (when I say gay males I mean effeminized and anally-receptive males and those who penetrate them) derive immense power from the heterosexual society. In fact they owe the heterosexual society their existence.

And, you know, that post dates from 2006.

But it hasn't aged.

Instead, with each passing day, its Truth becomes more obvious.

And more clear.

So :

Fighting.

My work is about Fighting.

Violent, Brutal, Bloody --

Fighting.

And that's what Aristotle is about too, when he discusses Manliness -- and the other Manly Moral Virtues :

Fighting.

Aristotle :

Aristotle : And so with Manliness : Again :

Fighting confers Manliness, while Manliness enables Fighting.

It's important to understand that essentially symbiotic relationship.

And Manliness and Fighting, working together, are Ethically Excellent, and Ethically Supreme.

So :

To Aristotle, every moral virtue, every ethical excellence, exists as a mean between a vice of excess, and one of defect.

For example, the moral virtue of Generosity.

The vice of excess is prodigality -- the tossing away of one's money.

The vice of defect is meanness -- the refusal to help a friend in need.

Similarly, and regarding the Supreme Moral Virtue and Ethical Excellence of Manliness, the vice of excess is over-confidence or rashness ;

while the vice of defect is UN-manliness, effeminacy, cowardice, which is the unwillingness to face pain, the fear of pain.

Aristotle :

[10] He that exceeds in fear is a coward, for he fears the wrong things, and in the wrong manner, and so on with the rest of the list. He is also deficient in confidence ; but his excessive fear in the face of pain is more apparent.

[11] The coward is therefore a despondent person, being afraid of everything ; but the Manly Man [ho andreios] is just the opposite, for confidence belongs to a sanguine temperament.

[12] The coward, the rash man, and the Manly Man are therefore concerned with the same objects, but are differently disposed towards them : the two former exceed and fall short, the last keeps the mean and the right disposition. The rash, moreover, are impetuous, and though eager before the danger comes they hang back at the critical moment ; whereas the Manly are keen at the time of action but calm beforehand.

[13] As has been said then, Manliness is the observance of the mean in relation to things that inspire confidence or fear, in the circumstances stated ; and it is confident and endures because it is noble [kalos] to do so or base [aischros -- shameful, base, dishonourable, ignoble] not to do so.

~Aristot. Nic. Eth. 3.7.11, translated by Rackham and myself.

So :

What Aristotle tells us is that the essence of the defect and vice of UN-manliness, effeminacy, cowardice -- is the coward's "excessive fear in the face of pain."

The essence of the vice of UN-manliness is the fear of pain and the inability to face pain.

"It is for Facing what is Painful that Men are called Manly."

And it's for fearing what is painful and refusing to face that pain -- that males are called, and behave as, UN-manly, effeminate, cowards.

How does a person learn to face pain ?

By facing pain.

Aristotle -- and the other Greeks -- all say so.

How does a young person, a young man, a youth -- learn to stand up to blows face to face ?

By standing up to blows face to face.

Again, the ancients all agree :

Moral Virtue -- all Moral Virtue -- is a question of habit.

Habit which has been carefully and ceaselessly inculcated since childhood.

And which results in what Cicero calls Fortitudo, which is Virtus, which is

Scorn of death and scorn of pain.

As Aristotle explains :

Aristotle :

[II] Virtue [αρετη -- excellence] being, as we have seen, of two kinds, intellectual and moral [διανοητικος kai ηθικοσ], intellectual excellence is for the most part both produced and increased by instruction, and therefore requires experience and time ; whereas moral or ethical excellence is the product of habit (ethos), and has indeed derived its name, with a slight variation of form, from that word. [a]

Footnote:

[a] Prof Rackham : It is probable that εθοσ, 'habit' and ηθοσ, 'character' (whence 'ethical,' moral) are kindred words.

Bill Weintraub : So that ηθικοσ αρετη -- ethical excellence -- is the product of εθοσ -- habit.

[2] And therefore it is clear that none of the moral excellences formed is engendered in us by nature, for no natural property can be altered by habit. For instance, it is the nature of a stone to move downwards, and it cannot be trained to move upwards, even though you should try to train it to do so by throwing it up into the air ten thousand times ; nor can fire be trained to move downwards, nor can anything else that naturally behaves in one way be trained into a habit of behaving in another way.

[3] The virtues [a] therefore are engendered in us neither by nature nor yet in violation of nature ; nature gives us the capacity to receive [b] them, and this capacity is brought to maturity by habit.

Footnotes:

[a] Prof Rackham : αρετη is here as often in this and the following Books employed in the limited sense of 'moral excellence' or 'goodness of character,' i.e. virtue in the ordinary sense of the term.

Bill Weintraub : Put differently, when Prof Rackham uses the English word 'virtue', he means moral virtue and/or ethical excellence ; and the most important and paramount ethical excellence, which comprehends all the others, is Manliness.

[b] Bill Weintraub : Aristotle says that nature gives us the capacity to receive the virtues -- and that capacity is discussed in our List of Warrior Theurgic Words, beginning with the word Form and continuing through Matter, Receptacle, Scission, and Substantiality.

And you must read that section -- that is, from Form through Substantiality -- which isn't long.

Nevertheless, you have to read it because, as Prof Rackham points out in his Introduction, Aristotle "assumes in his reader a knowledge of Plato's writings" -- and you have to have that knowledge in order to understand what Aristotle is saying.

[4] Moreover, the faculties given us by nature are bestowed on us first in a potential form ; we exhibit their actual exercise afterwards. This is clearly so with our senses : we did not acquire the faculty of sight or hearing by repeatedly seeing or repeatedly listening, but the other way about -- because we had the senses we began to use them, we did not get them by using them.

The virtues on the other hand we acquire by first having actually practised them, just as we do the arts. We learn an art or craft by doing the things that we shall have to do when we have learnt it : for instance, men become builders by building houses, harpers by playing on the harp. Similarly we become just by doing just acts, temperate by doing temperate acts, Manly by doing Manly acts.

[5] This truth is attested by the experience of states : lawgivers [such as the Spartan Lykourgos, father of the agogé,] make the citizens Manly by training them in habits of right action -- this is the aim of all legislation, and if it fails to do this it is a failure ; this is what distinguishes a good form of constitution from a bad one.

[6] Again, the actions from or through which any virtue is produced are the same as those through which it also is destroyed -- just as is the case with skill in the arts, for both the good harpers and the bad ones are produced by harping, and similarly with builders and all the other craftsmen : as you will become a good builder from building well, so you will become a bad one from building badly.

[7] Were this not so, there would be no need for teachers of the arts, but everybody would be born a good or bad craftsman as the case might be. The same then is true of the virtues. It is by taking part in transactions with our fellow-men that some of us become just and others unjust ; by acting in dangerous situations and forming a habit of fear or of confidence we become Manly or cowardly.

And the same holds good of our dispositions with regard to the appetites, and anger ; some men become temperate and good-tempered, others profligate [promiscuous] and irascible, by actually comporting themselves in one way or the other in relation to those passions.

In a word, our moral dispositions are formed as a result of the corresponding activities.

[8] Hence it is incumbent on us to control the character of our activities, since on the quality of these depends the quality of our dispositions. It is therefore not of small moment whether we are trained from childhood in one set of habits or another ; on the contrary it is of very great, or rather of supreme, importance.

~Aristot. Nic. Eth. 2.1.8, translated by Rackham and myself.

Book II, Chapter 2 :

Right action

[2.2.1] As then our present study, unlike the other branches of philosophy, has a practical aim (for we are not investigating the nature of virtue for the sake of knowing what it is, but in order that we may become good -- Manly -- , without which result our investigation would be of no use), we have consequently to carry our enquiry into the region of conduct, and to ask how we are to act rightly ; since our actions, as we have said, determine the quality of our dispositions.

[2] Now the formula 'to act in conformity with right principle' is common ground, and may be assumed as the basis of our discussion. (We shall speak about this formula later,[a] and consider both the definition of right principle and its relation to the other virtues.)

Footnote:

[a] Prof. Rackham : i.e., in Bk. 6. For the sense in which 'the right principle' can be said to be the virtue of Prudence see 6.13.5 note.

[3] But let it be granted to begin with that the whole theory of conduct is bound to be an outline only and not an exact system, in accordance with the rule we laid down at the beginning, that philosophical theories must only be required to correspond to their subject matter ; and matters of conduct and expediency have nothing fixed or invariable about them, any more than have matters of health.

[4] And if this is true of the general theory of ethics, still less is exact precision possible in dealing with particular cases of conduct ; for these come under no science or professional tradition, but the agents themselves have to consider what is suited to the circumstances on each occasion, just as is the case with the art of medicine or of navigation.

[5] But although the discussion now proceeding is thus necessarily inexact, we must do our best to help it out.

[6] First of all then we have to observe, that moral qualities are so constituted as to be destroyed by excess and by deficiency -- as we see is the case with bodily strength and health (for one is forced to explain what is invisible by means of visible illustrations). Strength is destroyed both by excessive and by deficient exercises, and similarly health is destroyed both by too much and by too little food and drink ; while they are produced, increased and preserved by suitable quantities.

[7] The same therefore is true of Manliness, Temperance, and the other virtues. The man who runs away from everything in fear and never endures anything becomes a coward. Similarly he that indulges in every pleasure and refrains from none turns out a profligate, and he that shuns all pleasure, as boorish persons do, becomes what may be called insensible. Thus Manliness and Temperance are destroyed by excess and deficiency, and preserved by the observance of the mean.

[8] But not only are the virtues both generated and fostered on the one hand, and destroyed on the other, from and by the same actions, but they will also find their full exercise in the same actions. This is clearly the case with the other more visible qualities, such as bodily strength : for strength is produced by taking much food and undergoing much exertion, while also it is the strong man who will be able to eat most food and endure most exertion.

[9] The same holds good with the virtues. We become temperate by abstaining from pleasures, and at the same time we are best able to abstain from pleasures when we have become temperate. And so with Manliness : we become Manly by training ourselves to despise and endure terrors, and we shall be best able to endure terrors when we have become Manly.

Pleasure and

[2.3.1] An index of our dispositions is afforded by the pleasure or pain that accompanies our actions. A man is temperate if he abstains from bodily pleasures and finds this abstinence itself enjoyable, profligate if he feels it irksome ; he is Manly if he faces danger with pleasure or at all events without pain, cowardly if he does so with pain.

In fact pleasures and pains are the things with which moral virtue is concerned.

For pleasure causes us to do base actions and pain causes us to abstain from doing noble actions [καλον].

[2] Hence the importance, as Plato points out, of having been definitely trained from childhood to like and dislike the proper things ; this is what good education means.

~Aristot. Nic. Eth. 2.2.1 - 2.3.2, translated by Rackham and myself.

So :

These are Aristotle's key points regarding the role of habit in inculcating Manliness :

So :

At its most basic, a boy becomes Manly by learning to face pain ; a boy becomes a coward by running away from pain.

That's what happens.

Most of you reading this have spent your lives, in fear, running away from pain -- specifically, the fear engendered by the potential pain of a fist to your face.

As a consequence, you're not Manly ; and you cannot, no matter how hard you try, attract to yourself -- a Man who is Manly.

That's the problem.

You could solve it ; but you're afraid to.

Once again, how does a young person, a young man, a youth -- learn to stand up to blows face to face ?

By standing up to blows face to face.

Functionality and consciousness

Once again :

This, epitomized, is what Aristotle says about how Men achieve the Moral Virtue of Manliness :

By dispositions he means moral dispositions.

Manliness is a moral disposition -- it is the moral disposition to behave in a Manly fashion.

It is the disposition to Fight.

Not to run.

But to Fight.

My work is about Fighting.

Cicero agrees with all of that.

Which is why he says

What is best for Man is that which is desirable in and of itself, has its source in Virtue and is based on Virtue, is of itself praiseworthy, and in fact should be described as the ONLY, rather than the highest, Good :

Manliness.

And every other Roman agrees.

Which is why the great historian of the Roman Revolution, Ronald Syme, says that :

"[At Rome,] Virtus itself stands at the peak of the hierarchy, transcending mores."

~Syme, The Roman Revolution, 1939, 157.

Virtus -- Manliness -- stands at the peak of the hierarchy, transcending all other morals, all other virtues.

The Moral Virtue of Manliness, which is the Ardent Willingness and Requisite Ability to Fight, to Fight Man2Man, and which is the ethikos areté, the Supreme Moral Virtue, the Supreme Ethical Excellence, is, according to Aristotle, primarily about the Man's willingness -- a willingness which is a moral trait -- about the Man's willingness to face pain.

Aristotle :

Though Manliness is concerned with feelings of confidence and fear, it is not concerned with both alike, but more with the things that inspire fear ; for he who is undisturbed in face of these and bears himself as he should towards these is more truly Manly than the man who does so towards the things that inspire confidence. It is for facing what is painful, then, that Men are called Manly. Hence also, then, Manliness involves pain, and is justly [δικαιος] praised ; for it is harder to face what is painful [λυπηρος] than to abstain from what is pleasant.

~Aristot. Nic. Eth. 1117a, translated by WD Ross and myself.

So :

"It is for Facing what is Painful that Men are called Manly."

That is, It is for Facing what is Painful that Men are deemed to possess Manliness :

Aristotle :

Though Manliness is concerned with feelings of confidence and fear, it is not concerned with both alike, but more with the things that inspire fear ; for he who is undisturbed in face of these and bears himself as he should towards these is more truly Manly than the man who does so towards the things that inspire confidence. It is for facing what is painful, then, that Men are called Manly. Hence also, then, Manliness involves pain, and is justly [δικαιος] praised ; for it is harder to face what is painful [λυπηρος] than to abstain from what is pleasant.

~Aristot. Nic. Eth. 1117a, translated by WD Ross and myself.

Now :

When Aristotle speaks of over-confidence or rashness, does he mean too much Manliness ?

Answer :

No.

Aristotle explains at length what he means by "rashness" in his extended and extremely useful discussion of Manliness, which begins at Book 3.6.1 of the Nikomachean Ethics.

Basically, rashness or over-confidence is a false Manliness.

It appears at first to be Manly, but on close inspection, it isn't.

Here's part of what Aristotle says :

[a] i.e., in situations not really formidable.

[9] Hence most rash men really are cowards at heart, for they make a bold show in situations that inspire confidence, but do not endure terrors.

So the rash man is actually an impostor, "who pretends to a manliness which he does not possess," being really a coward at heart.

A rash male cannot endure terrors, he fears and cannot face pain.

The Manly Man can and does.

Aristotle :

[T]he Manly Man is proof against fear so far as man may be. Hence although he will sometimes fear even terrors not beyond man's endurance, he will do so in the right way, and he will endure them as principle dictates, for the sake of what is noble [καλον] [a] ; for that is the end at which virtue aims.

[a] i.e., the rightness and fineness of the act itself, cf. 7.13 ; 8.5,14 ; 9.4 ; and see note on 1.3.2. This amplification of the conception of virtue as aiming at the mean here appears for the first time : we now have the final as well as the formal cause of virtuous action.

Bill Weintraub : The "formal cause" of virtuous action is the individual's "aiming at the mean" between excess and deficiency ; the "final cause" of virtuous action is the individual's decision to act for the sake of what is καλον -- kalon -- that is, what is both Morally Beautiful and Morally Noble.

Which leads us to Prof Rackham's :

Note on 1.3.2 :

Καλον is a term of admiration applied to what is correct, especially (1) bodies well shaped and works of art or handicraft well made (see iii. vii. 6), and (2) actions well done ; it thus means (1) beautiful, (2) morally right. For the analogy between moral and material correctness see ii. vi. 9 :

[2.6.9] If therefore the way in which every art or science performs its work well is by looking to the mean and applying that as a standard to its productions (hence the common remark about a perfect work of art, that you could not take from it nor add to it -- meaning that excess and deficiency destroy perfection, while adherence to the mean preserves it) -- if then, as we say, good craftsmen look to the mean as they work, and if moral virtue, like nature, is more accurate and better than any form of art, it will follow that moral virtue has the quality of hitting the mean.

~Aristot. Nic. Eth. 3.7.2, translated by Rackham and myself.

And it's Prof Rackham who tells us that Aristotle is "a thinker and writer of extreme precision."

And that's what 2.6.9 is about :

"moral virtue -- Manliness -- has the quality of hitting the mean"

and the mean is Kalon -- Manliness :

Bodies well made, through Actions well done.

The Actions -- the Fightings -- are Noble, Honourable, and Beautiful.

And confer Moral -- aka Ethical -- Supremacy.

Thus, because "moral virtue, like nature, is more accurate and better than any form of art, it will follow that moral virtue has the quality of hitting the mean."

And to see the truth of what Aristotle's saying -- that Moral Virtue -- which is Manly Virtue -- which is Manliness -- is more accurate and better than any form of art, just look at this pic of the Combative Congregation :

Aristotle :

And the Manly Man will endure terrors as principle dictates, for the sake of what is Noble -- Καλον -- for that is the end at which moral virtue aims.

It is the Fighter's willingness to endure the terrors, to endure the pain -- to face the pain and take the pain -- which makes the act Beautiful.

Uniquely Beautiful.

Noble and Beautiful.

Aristotle :

What form of death then is a test of Manliness [andreia]? Presumably that which is the noblest [kallistos]. Now the noblest form of death is death in battle [polemos -- battle, fight, war], for it is encountered in the midst of the greatest and most noble of dangers [megistos kai kallistos kindunos]. And this conclusion is borne out by the principle on which public honours [Tima] are bestowed in republics and under monarchies.

The Manly Man [ho andreios], therefore, in the proper sense of the term, will be he who fearlessly confronts a noble death [kalos thanatos], or some sudden peril that threatens death ; and the perils of polemos -- battle, fight, war -- answer this description most fully.

Aristotle :

And every activity aims at the end [telos -- fulfillment, completion, consummation, result] that corresponds to the disposition of which it is the manifestation. So it is therefore with the activity of the Manly Man [ho andreios] : his Manliness is noble [kalos] ; therefore its consummation is nobility [kalon], for a thing is defined by its consummation ; therefore the Manly Man endures the terrors and dares the deeds that manifest Manliness, for the sake of that which is noble.

~Aristotle, Nikomachean Ethics, 1115a-6, translated by Rackham and myself.

Again, Kalos at its most basic means both Noble and Beautiful.

And it's pain -- the pain of Fight -- and the Fighter's Willingness to Face and Take that Pain -- which confers Nobility and Beauty.

I'll have more to say about this -- below.

For now :

The end at which moral virtue -- ethical excellence -- aims, is Nobility -- Καλον -- Kalon ; and, as we discussed The Combative Congregation, Kalon is a term of admiration for bodies well made, actions well done.

Καλον -- Moral Nobility -- which is Manliness.

And the action in question is always Fighting :

Aristotle :

It is possible to fear terrors too much, and too little ; and also to fear things that are not fearful as if they were fearful.

Error arises either from fearing what one ought not to fear, or from fearing in the wrong manner, or at the wrong time, or the like ; and similarly with regard to occasions for confidence.

The Manly Man then is he that endures or fears the right things and for the right purpose and in the right manner and at the right time, and who shows confidence in a similar way.

This is an important statement -- and a statement of extreme precision.

To understand its importance, we need to contrast it with what Aristotle tells us about the opposite of Moral Virtue -- which is Moral Evil :

[16] And it is a mean state between two vices, one of excess and one of defect. Furthermore, it is a mean state in that whereas the vices either fall short of or exceed what is right in feelings and in actions, virtue ascertains and adopts the mean.

[17] Hence while in respect of its substance and the definition that states what really is in essence virtue is the observance of the mean, in point of excellence and rightness it is an extreme. [aristos, eu, akros]

[18] Not every action or emotion however admits of the observance of a due mean. Indeed the very names of some directly imply evil, for instance malice, shamelessness, envy, and, of actions, adultery, theft, murder. All these and similar actions and feelings are blamed as being bad in themselves ; it is not the excess or deficiency of them that we blame.

It is impossible therefore ever to go right in regard to them -- one must always be wrong ; nor does right or wrong in their case depend on the circumstances, for instance, whether one commits adultery with the right woman, at the right time, and in the right manner; the mere commission of any of them is wrong [amartano].

[19] One might as well suppose there could be a due mean and excess and deficiency in acts of injustice or cowardice or profligacy, which would imply that one could have a medium amount of excess and of deficiency, an excessive amount of excess and a deficient amount of deficiency.

[20] But just as there can be no excess or deficiency in temperance and justice because the mean is in a sense an extreme, so there can be no observance of the mean nor excess nor deficiency in the corresponding vicious acts mentioned above, but however they are committed, they are wrong; since, to put it in general terms, there is no such thing as observing a mean in excess or deficiency, nor as exceeding or falling short in the observance of a mean.

~Aristot. Nic. Eth. 2.6.15-18, translated by Rackham.

Contrast what Aristotle says about adultery -- which is a form of sexual promiscuity -- and which "must always be wrong" -- that it doesn't matter whether the act is done "with the right woman, at the right time, and in the right manner; the mere commission of any of them is wrong [amartano]" --

With what he says about Manliness :

The Manly Man then is he that endures or fears the right things and for the right purpose and in the right manner and at the right time, and who shows confidence in a similar way.

What the adulterer does is always wrong.

While what the Manly Man does is by definition always Morally Upright and Morally Excellent.

Aristotle :

For the Manly Man feels and acts as the circumstances merit, and as principle may dictate.

And every activity aims at the end [telos -- fulfillment, completion, consummation, result] that corresponds to the disposition [ -- in this case, Manliness -- ] of which it is the manifestation. So it is therefore with the activity of the Manly Man [ho andreios] : his Manliness is noble [kalos] ; therefore its consummation is nobility [kalon], for a thing is defined by its consummation ; therefore the Manly Man endures the terrors and dares the deeds that manifest Manliness, for the sake of that which is noble.

~Aristotle, Nikomachean Ethics, 1115a-6, translated by Rackham and myself.

And Manliness, again, is the chief moral virtue, the most important ethical excellence, in Aristotle's system of Ethical Virtue in The Nicomachean Ethics, which Rackham tells us is the most important exposition of ancient Greek Pagan and Hellenist Ethics -- which we have :

And what makes it so important is first of all the extreme precision of Aristotle's thought and writing, and the fact that Aristotle makes constant reference to what the Greeks of his time actually believed and how they actually behaved.

To them, as to the Romans and the Kelts and the Teutons etc, Manliness is the most important Moral Virtue -- by far.

Manliness -- Fighting Manhood -- and its accompanying Fighting -- is the Summum Bonum -- the Supreme Good.

So :

My work is about Fighting.

Because Fighting is the Supreme Good.

Aristotle :

[T]he Manly Man is proof against fear so far as man may be. Hence although he will sometimes fear even terrors not beyond man's endurance, he will do so in the right way, and he will endure them as principle dictates, for the sake of what is noble [καλον] ; for that is the end at which virtue aims.

~Aristot. Nic. Eth. 3.7.2, translated by Rackham and myself.

So :

"It is for Facing what is Painful that Men are called Manly."

That is, It is for Facing what is Painful that Men are deemed to possess Manliness.

And the Manly Man will endure terrors as principle dictates, for the sake of what is Noble -- Καλον -- for that is the end at which moral virtue aims.

And Manliness, again, is the chief moral virtue, the most important ethical excellence, in Aristotle's system of Ethical Virtue in The Nicomachean Ethics, which Rackham tells us is the most important exposition of ancient Greek Pagan and Hellenist Ethics -- which we have :

And what makes it so important is that Aristotle makes constant reference to what the Greeks of his time actually believed and how they actually behaved.

To them, as to the Romans and the Kelts and the Teutons etc, Manliness is the most important Virtue -- by far.

Manliness -- Fighting Manhood -- and its accompanying Fighting -- is the Summum Bonum -- the Supreme Good.

So : Let's look at another picture of Fighters and Fighting, another picture of Manliness, which is Kalon -- both Manly Beauty and Moral Nobility :

And you can see once again that Kalon is

Καλον :

Kalon comprises Moral Nobility, Manly Honour, and Manly Beauty.

Would these guys have Moral Nobility, Manly Honour, and Manly Beauty -- to the Greeks ?

Absolutely.

Their Moral Nobility stems from their Willingness and Ability to Fight --

Specifically, to stand up to blows face to face.

Which they clearly have done.

Again :

So :

Fighting confers Moral Nobility.

In addition, Fighting as they have has generated and added to their Manly Honour ;

While Fighting has given them a Manly Beauty which is both physical and spiritual.

And notice that the Fighter and Warrior on the right has tattooed on his arm, SPQR -- SENATUS POPULUS QUE ROMANUM -- The Senate and People of Rome -- and what appears to be a Roman Helmet, topped by a Victory Wreath.

While the Fighter on the left has his hair done up in a top-knot.

Which was the style among Imperial Roman Boxers :

These two truly Magnificent and Manly Men aren't the only MMA Fighters to have symbols of ancient Warriors on their flesh.

Many -- many -- have them.

For example :

And in the pic below, you can see that the Fighter on the left bears on his body a succinct statement of a belief which was held virtually universally by Men in the ancient world : Death before Dishonour.

As I say, that belief was held virtually universally by Men in the ancient world, including Cicero and Aristotle :

Aristotle :

Manliness . . . is prompted by a virtue, namely the sense of shame [aidos], and by the desire for something noble [kalon], namely honor [timé], and the wish to avoid disgrace [aischros -- dishonour, disgrace, moral ugliness].

The Ethical Supremacy conferred by Fighting Men and their Fighting Manhood is the source of all Manly Honour.

And of Nobility.

That which is Noble -- Nobility -- Καλον -- is, like Honour, inextricably intertwined with Fighting Men and their Fighting Manhood.

Because Nobility is Selflessness -- Selflessness-in-Fight.

Aristotle :

And every activity aims at the end [telos -- fulfillment, completion, consummation, result, objective] that corresponds to the disposition [ moral disposition -- in this case, Manliness -- ] of which it is the manifestation. So it is therefore with the activity of the manly man : his manliness is noble [kalos] ; therefore its consummation is nobility [kalon], for a thing is defined by its consummation ; therefore the manly man endures the terrors and dares the deeds that manifest manliness, for the sake of that which is noble.

~Aristotle, Nikomachean Ethics, 1115a-6, translated by Rackham and myself.

Most of you don't know what being a Man is about.

You don't.

But it's about Fighting.

That's what it's about.

It's about Fighting.

And choosing Honour -- which is Manliness --

While scorning pain and death.

As Aristotle says, "The Manly Man endures the terrors and dares the deeds that manifest Manliness, for the sake of that which is Noble -- Καλον."

And you endure the terrors and dare the deeds -- through Fighting.